C15th Czech manuscript for a recipe in Old CZECH – Very early printed proof copy of an unknown calendar in CZECH – all in a 1484 edition of Simon de Cassia in contemporary binding.

£0.00

Out of stock

Comprising:

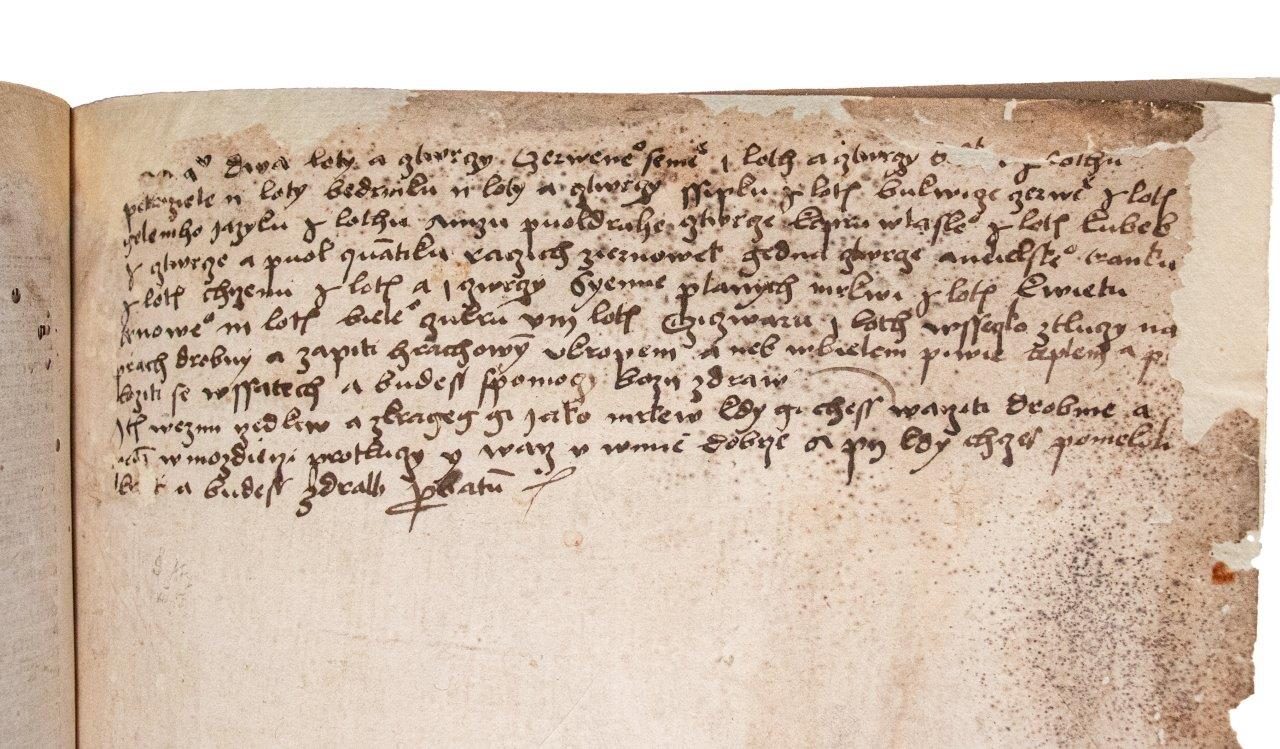

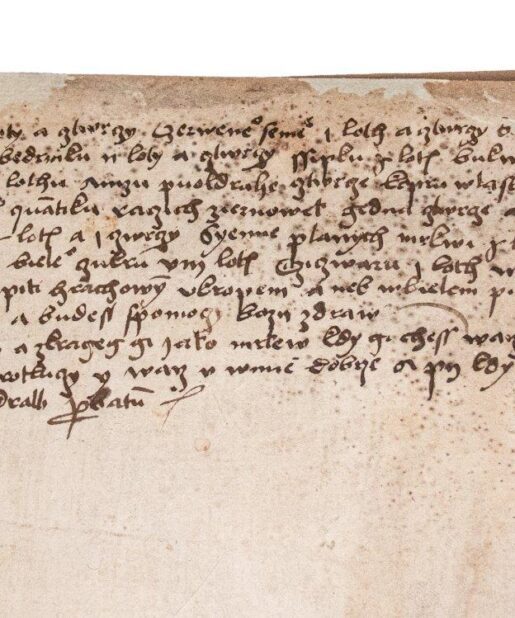

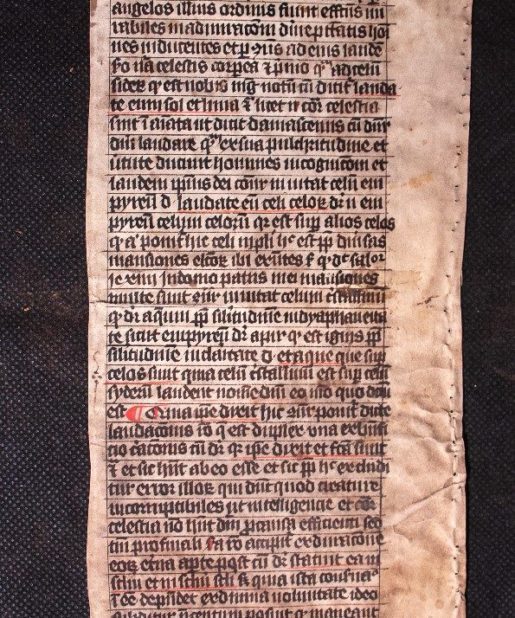

- Manuscript recipe for kidney stones in old Czech – C15th

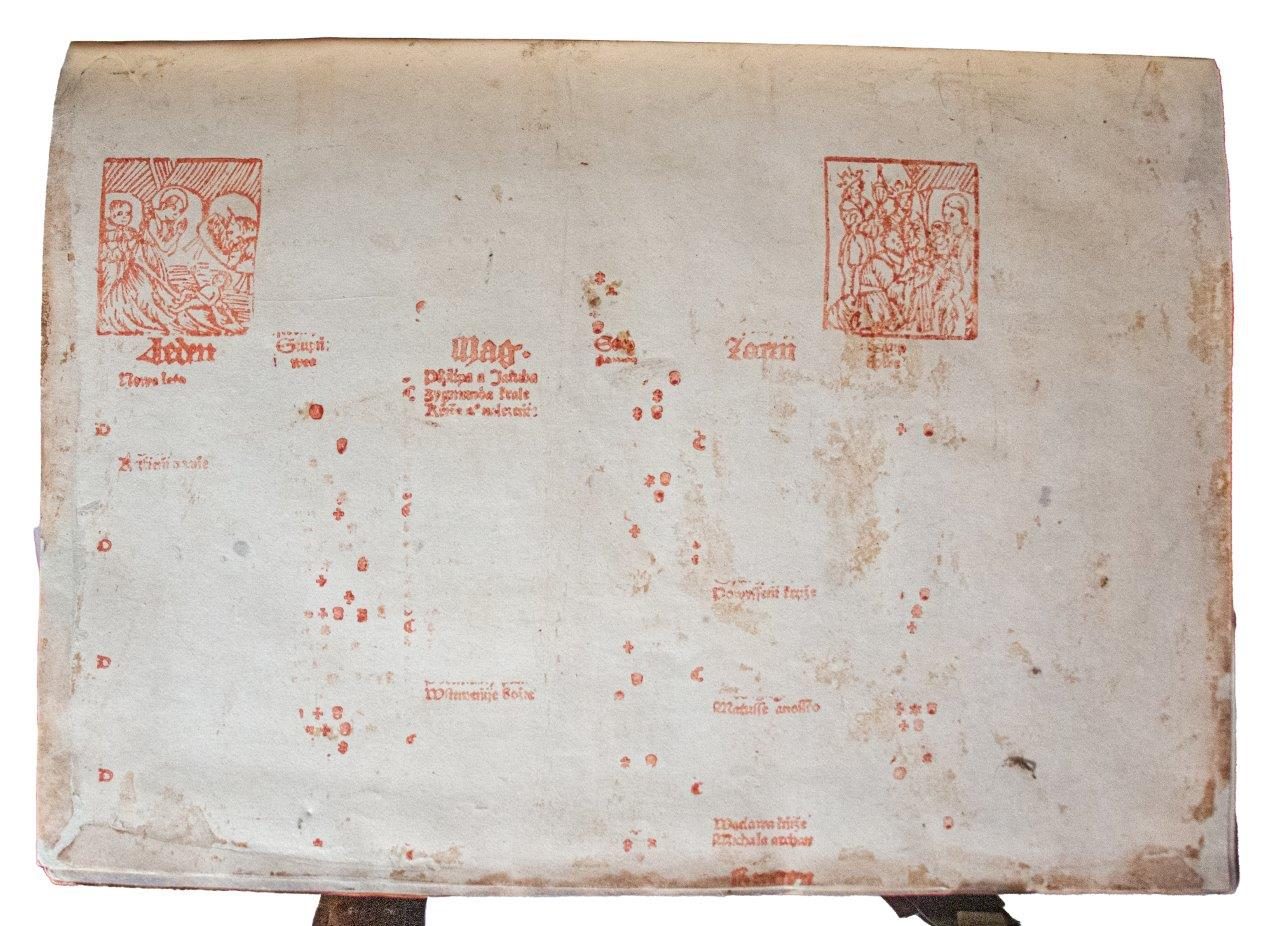

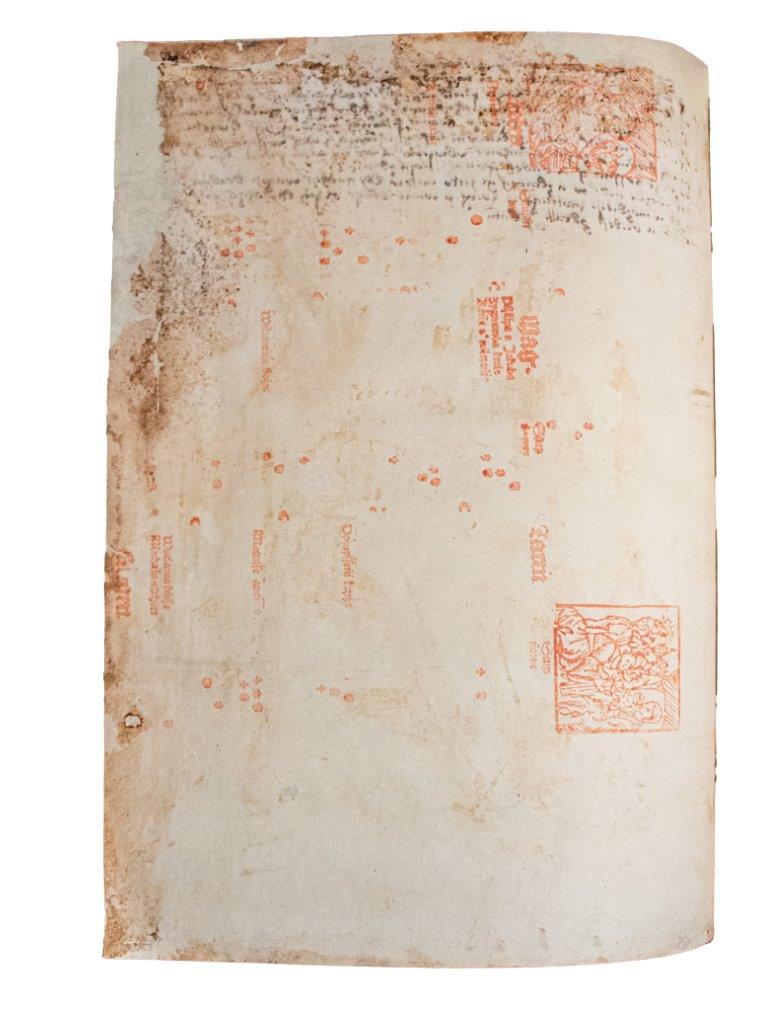

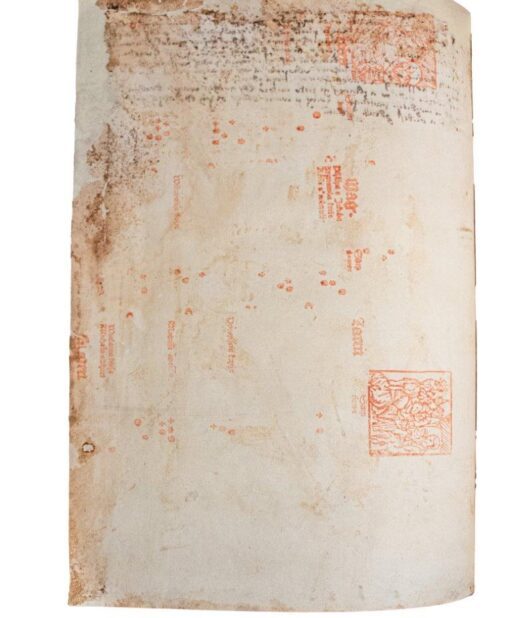

- 2 endleaves of C15th printed Czech ‘blood-letting’ calendars, probably the earliest or second earliest recorded.

- Incunable in original binding of Simon de Cassia

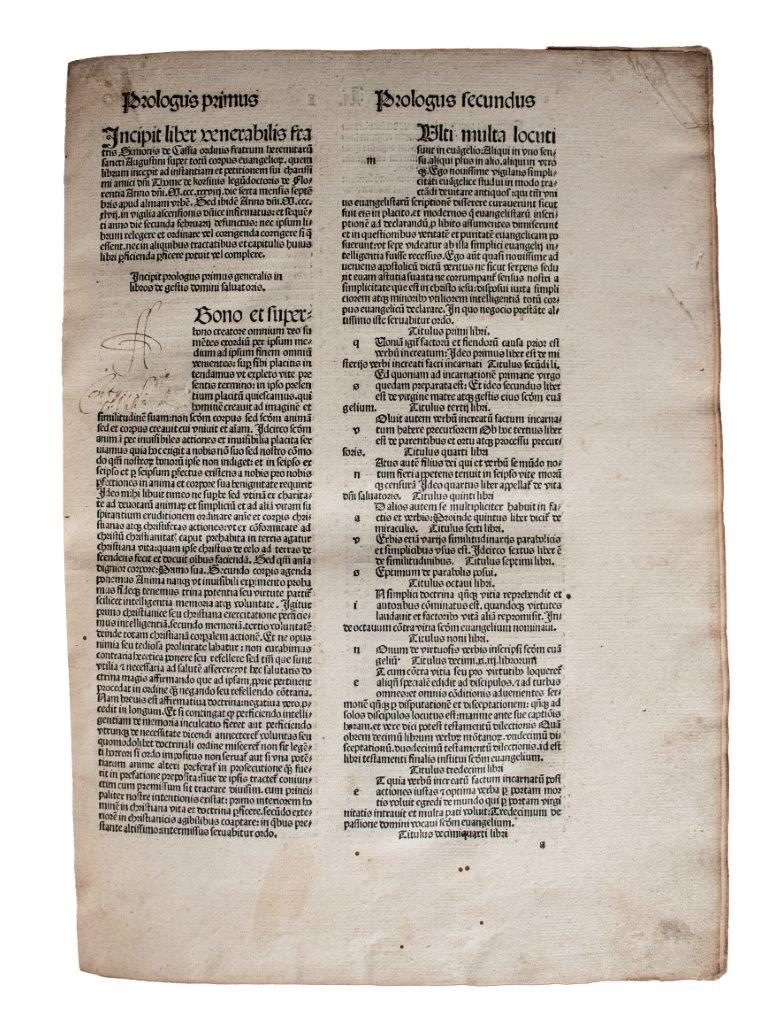

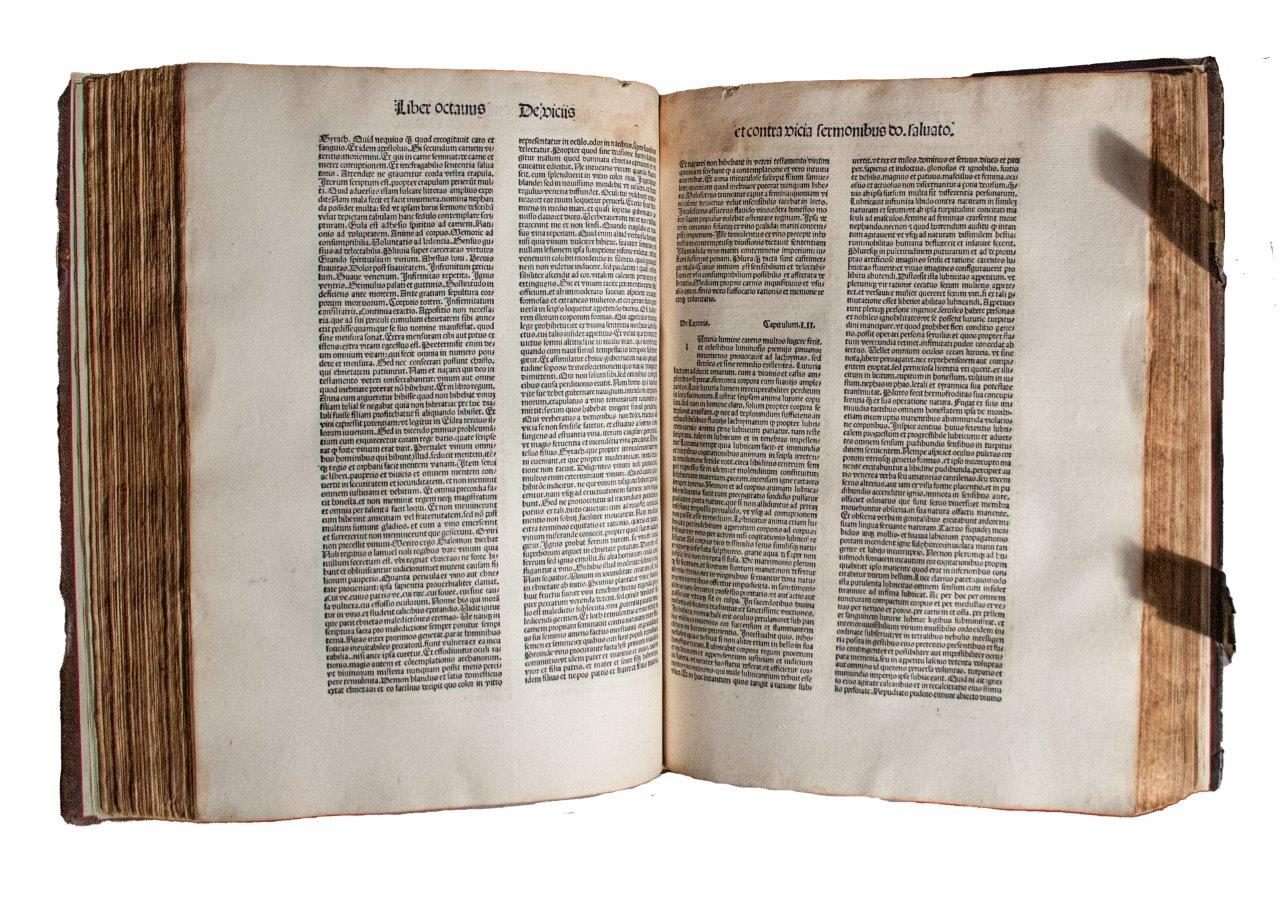

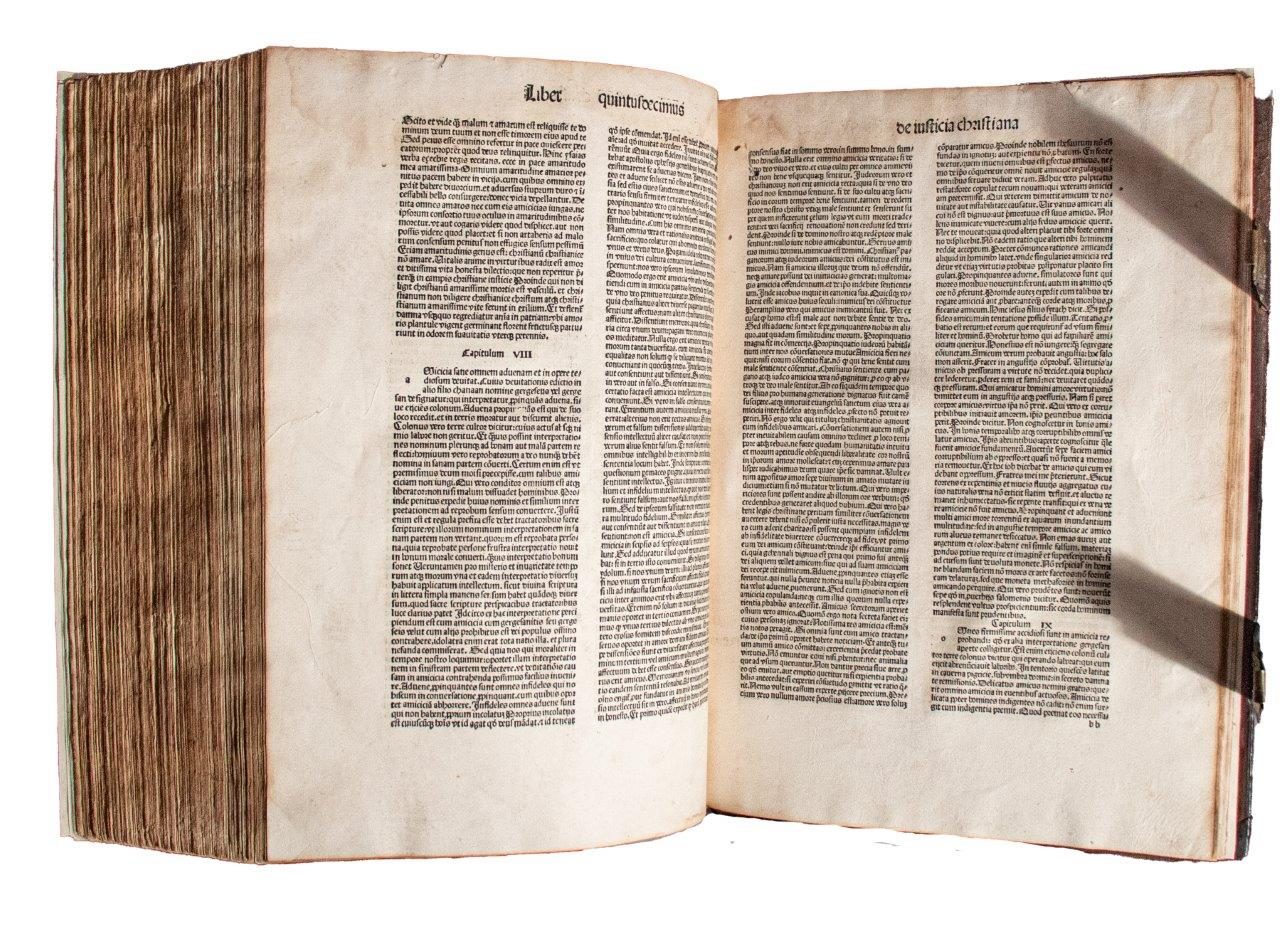

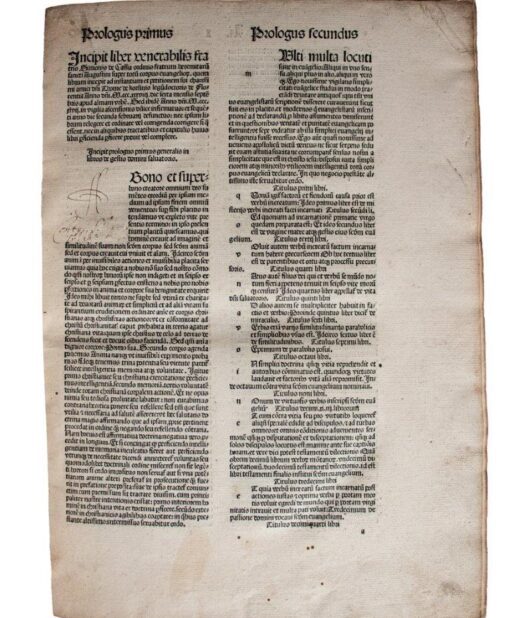

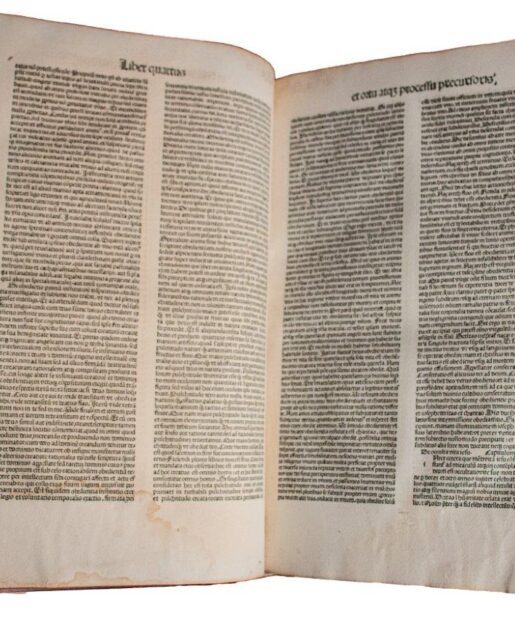

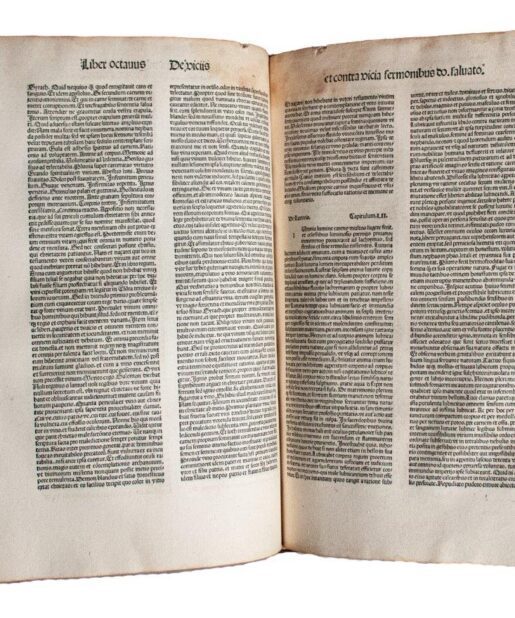

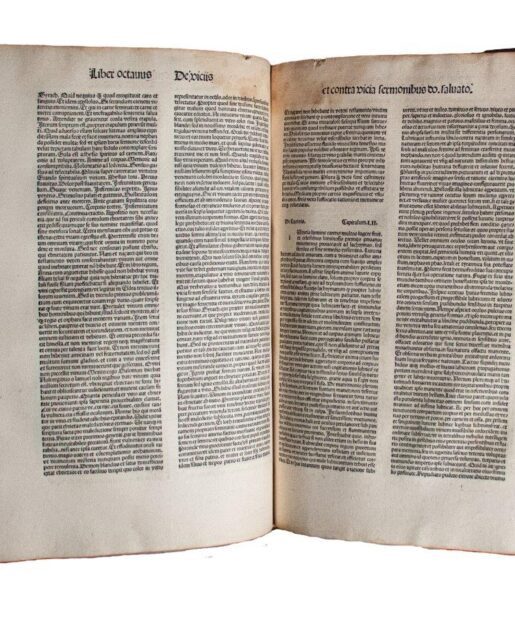

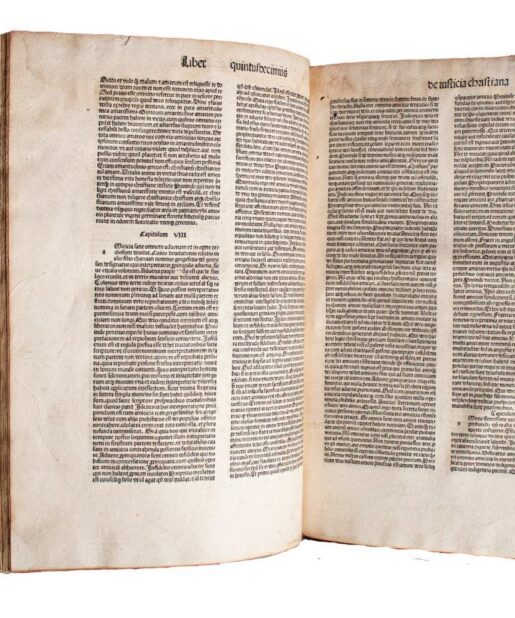

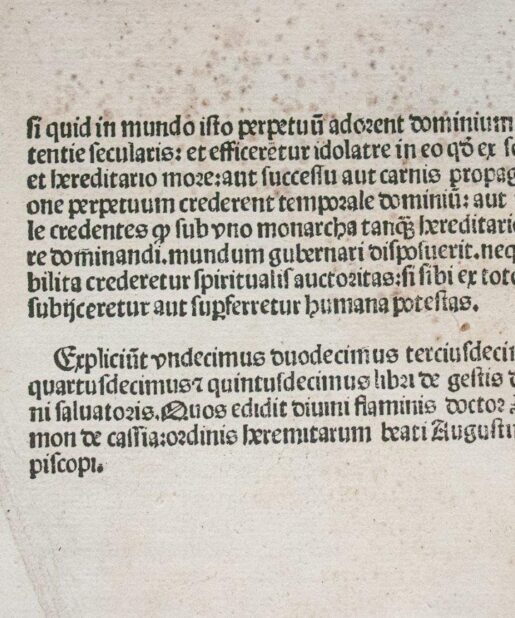

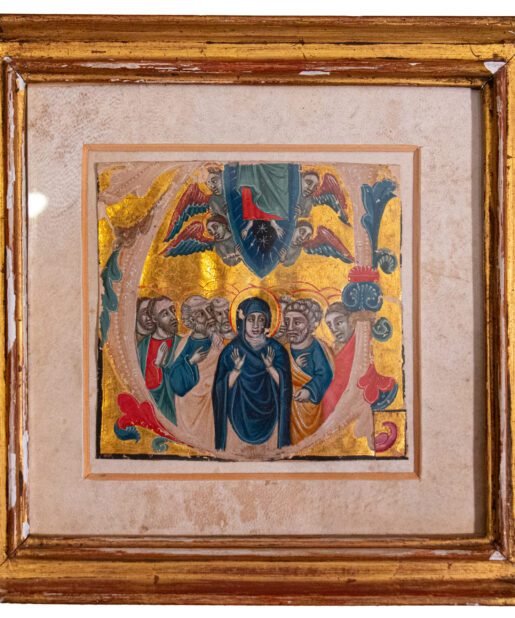

Simon de Cassia. Expositio super totum corpus Evangeliorum.

O.O., Dr. u. J. (probably Strasbourg, Johann Prüss, around 1484-87).

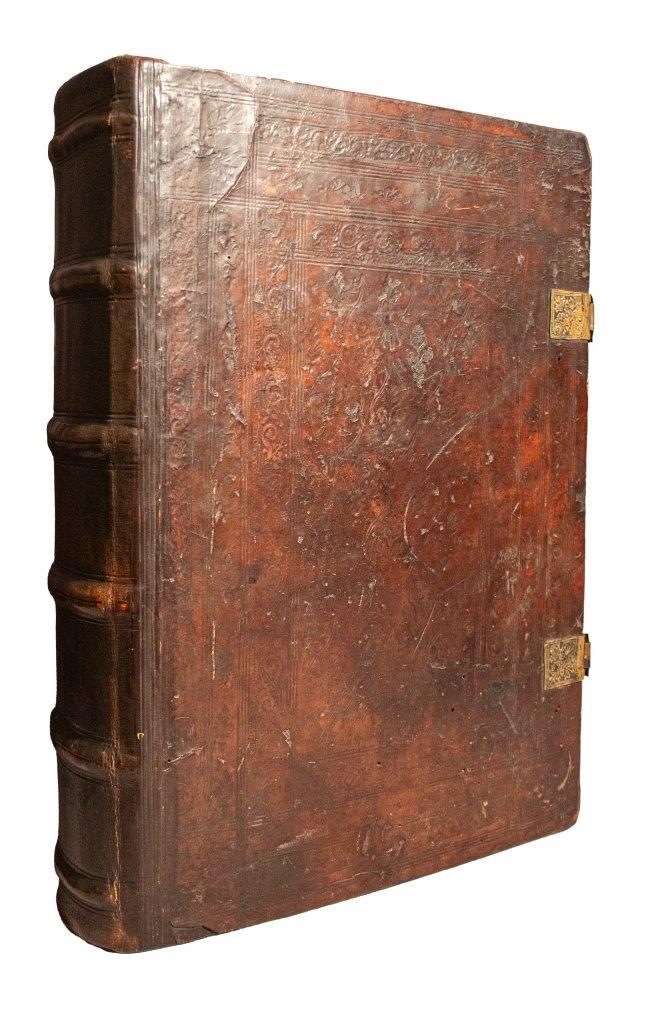

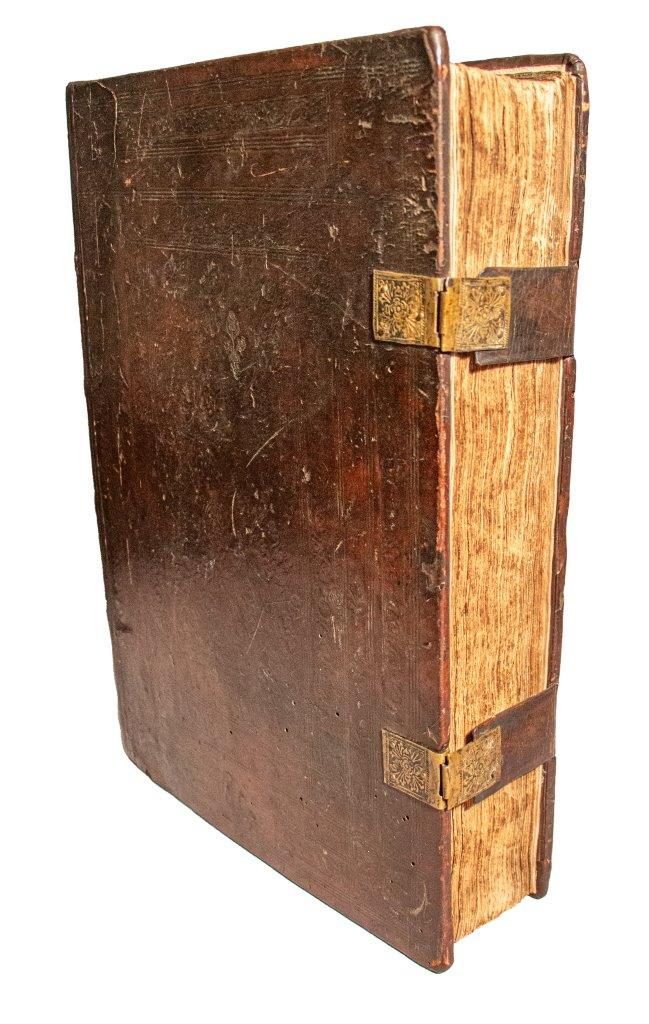

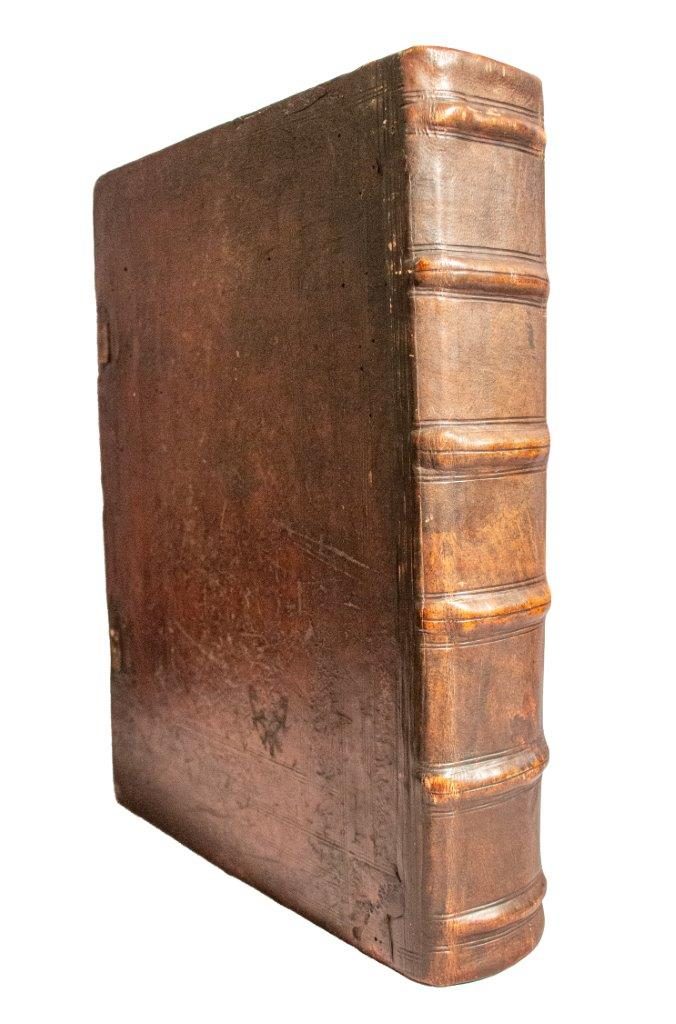

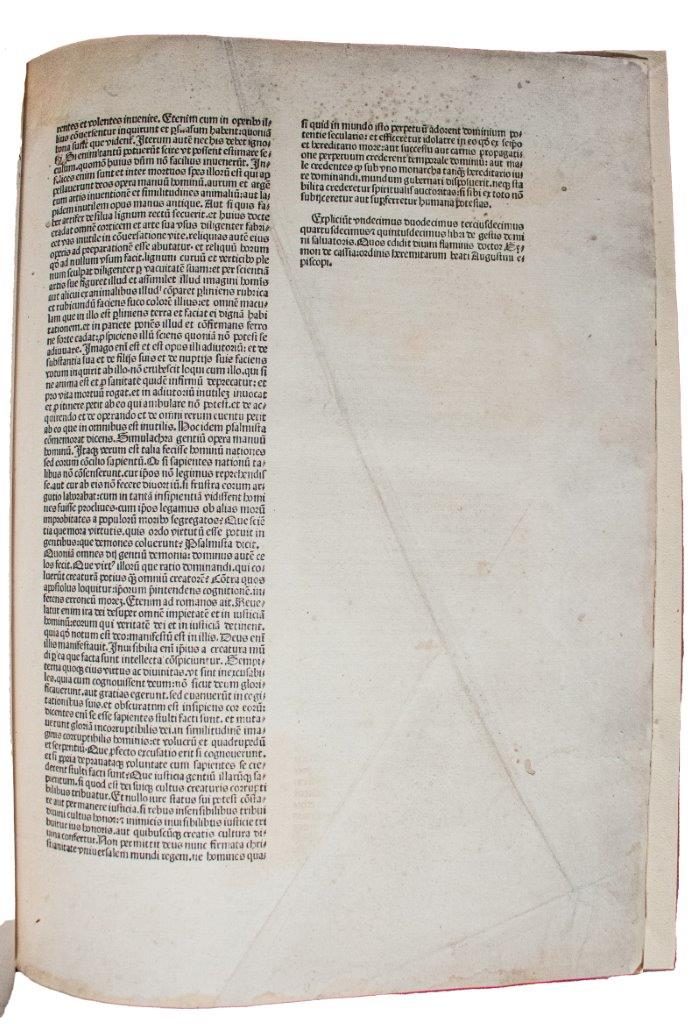

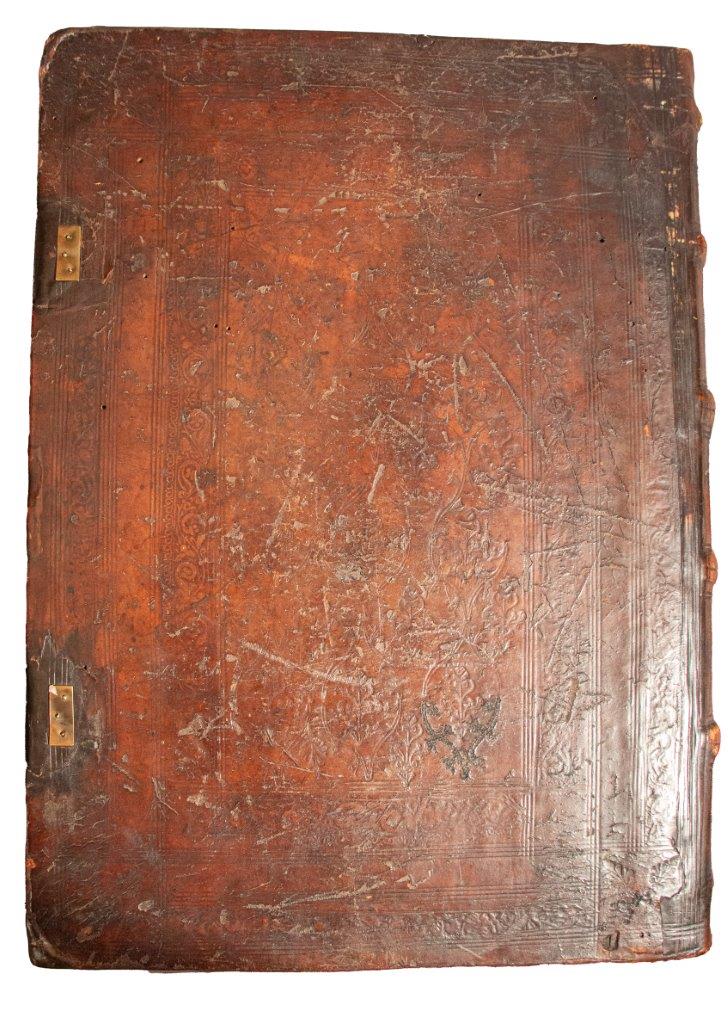

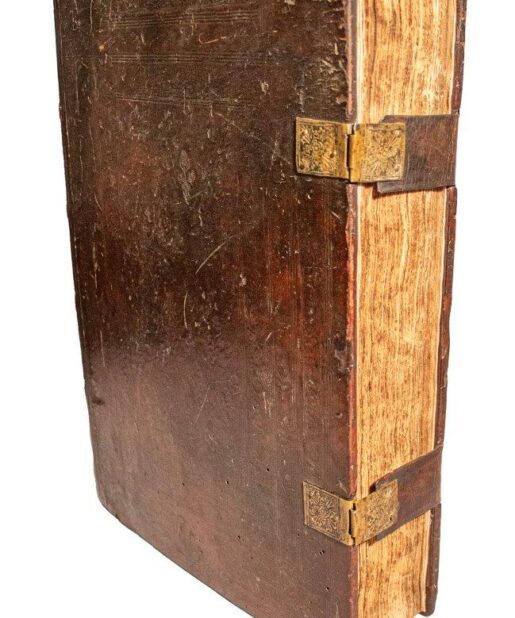

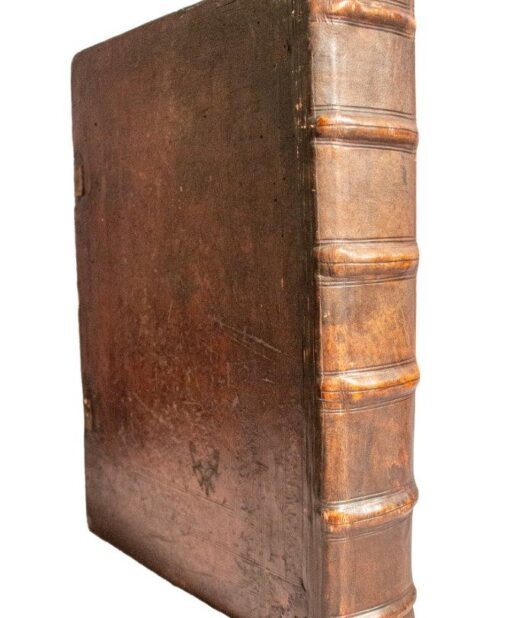

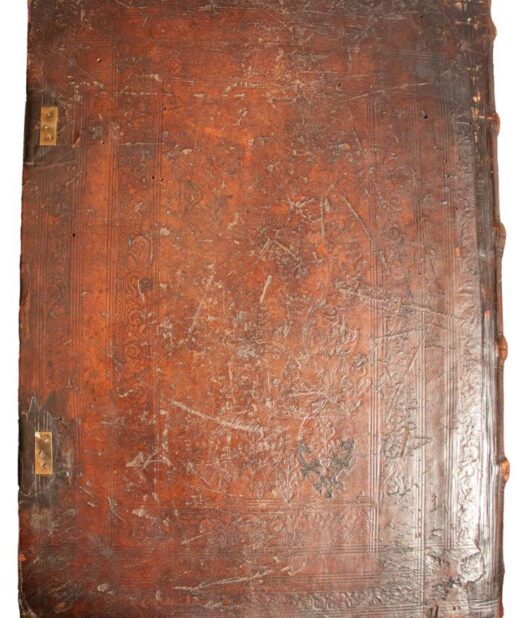

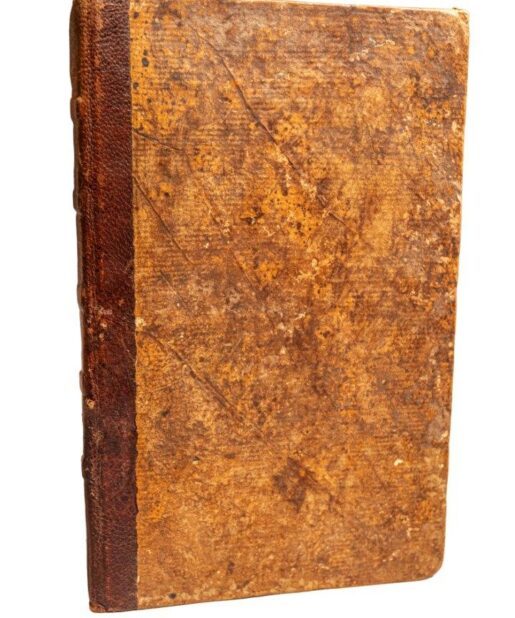

Folios 385 (instead of 386) leaves (without the first blank). Restored contemporary blind-stamped on wooden boards with 2 metal clasps (spine renewed, with wormholes, somewhat rubbed and bumped). First and only Latin incunabula edition. Goff S 522. IGI 8994. BMC I, 120. GW M42190. BSB S-401. Wetzer/Welte IV, 1482 (under Fidatus).

The attribution of the print to Johann Prüss is not entirely clear, Peter Drach in Speyer is also a possible printer.

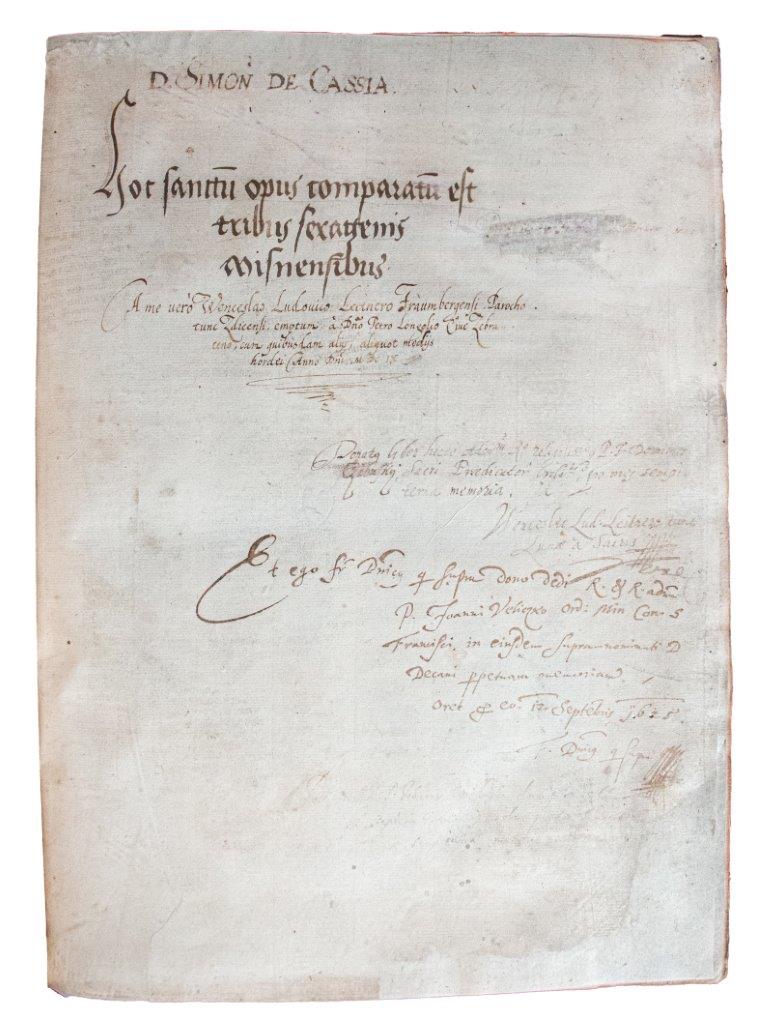

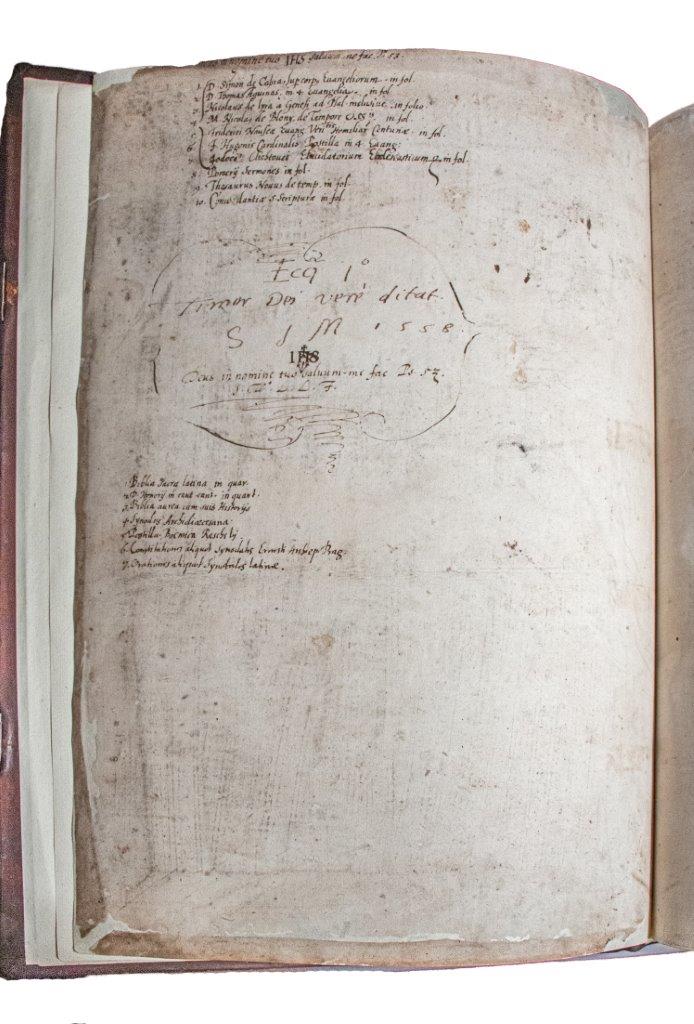

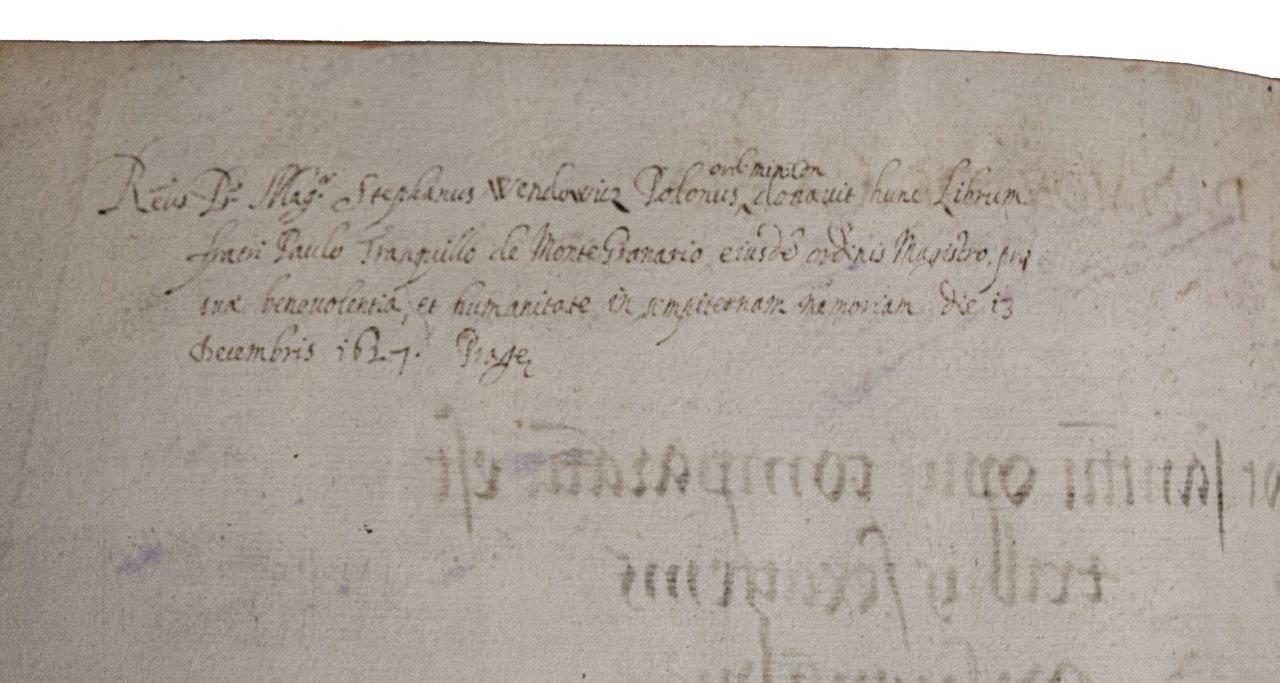

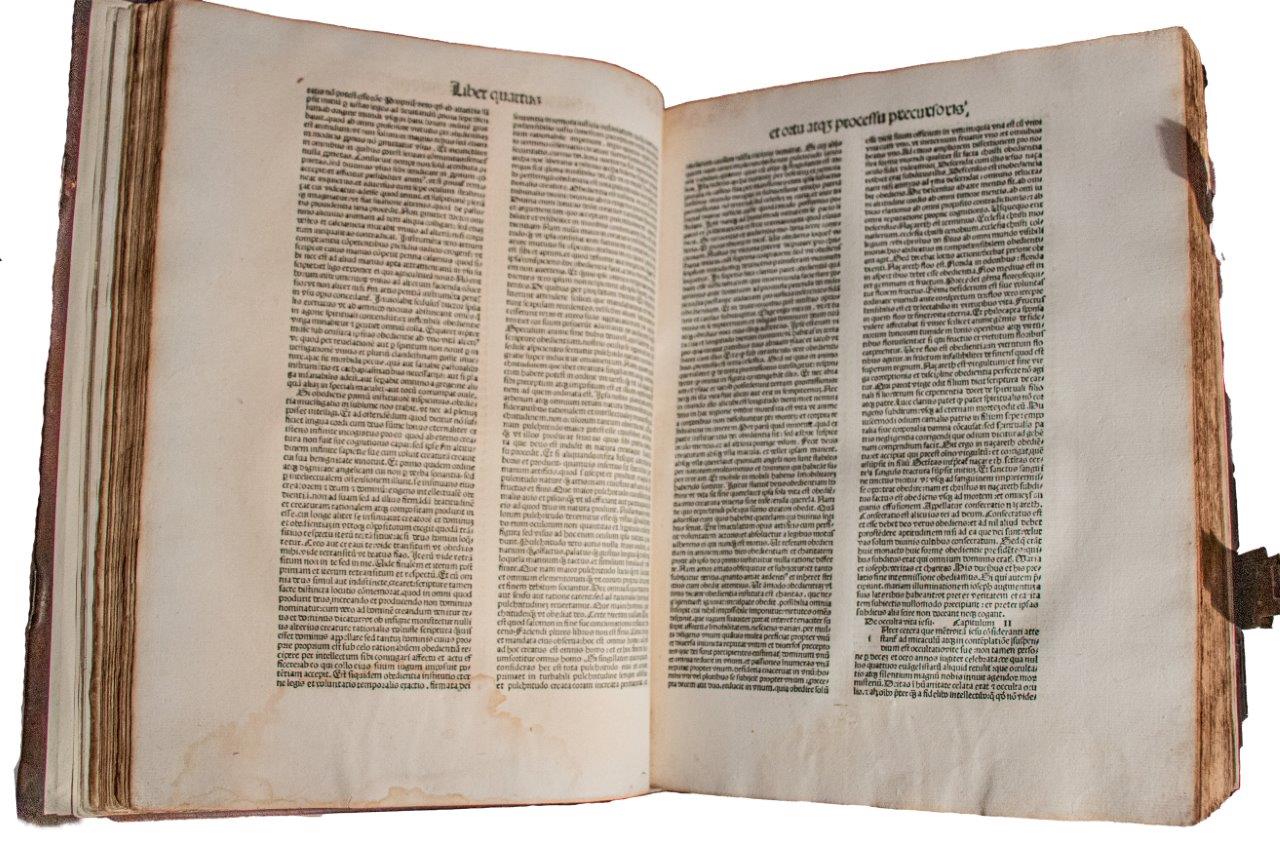

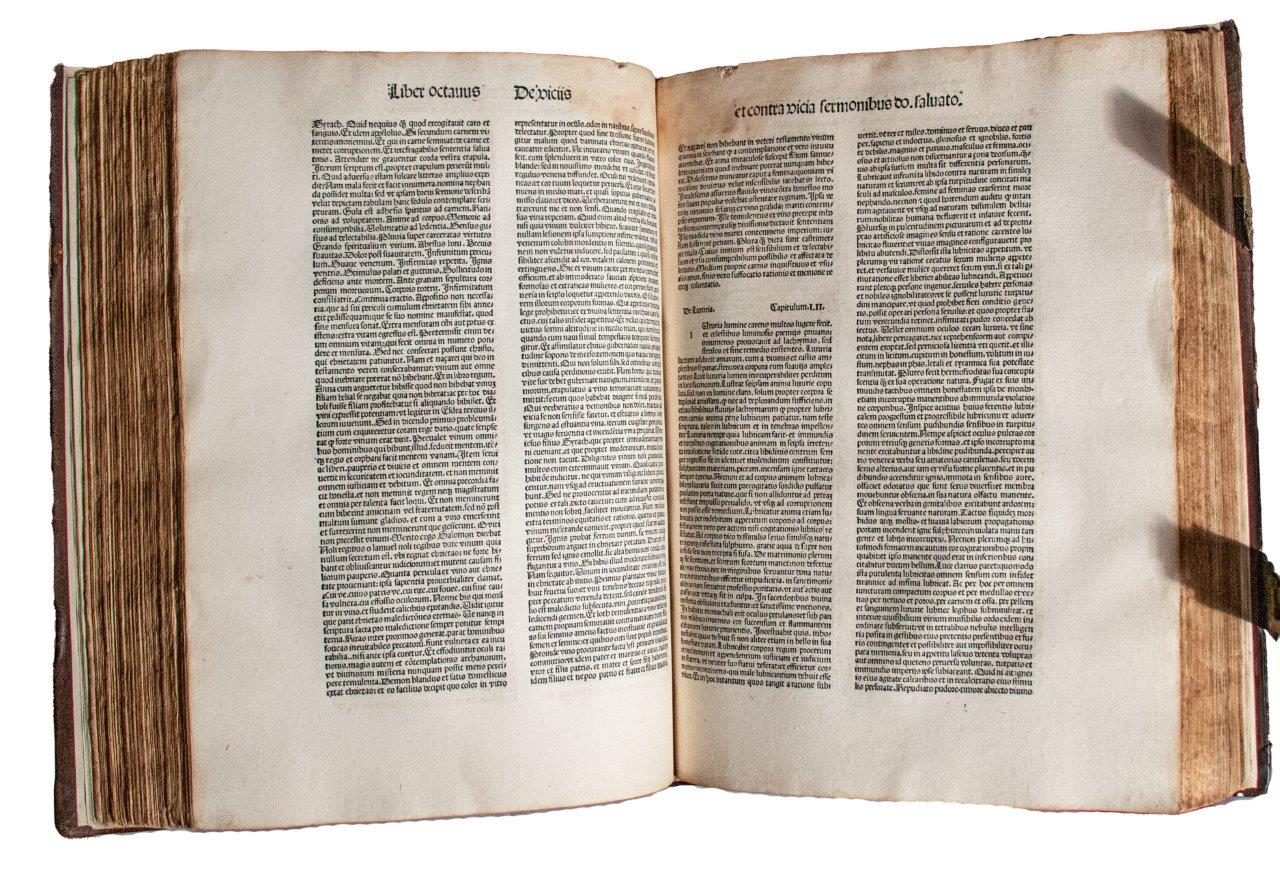

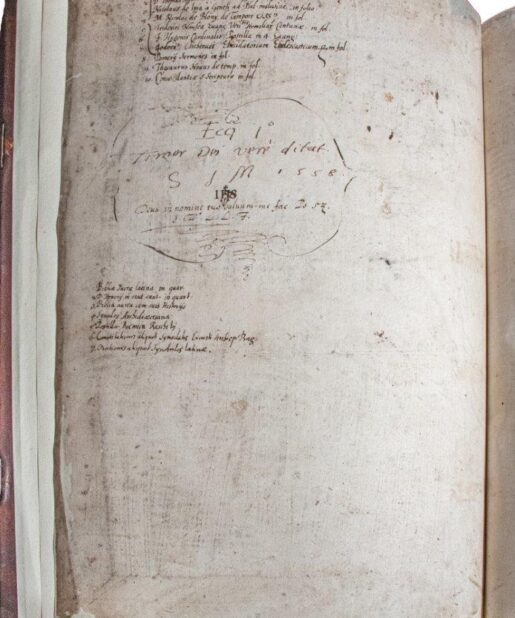

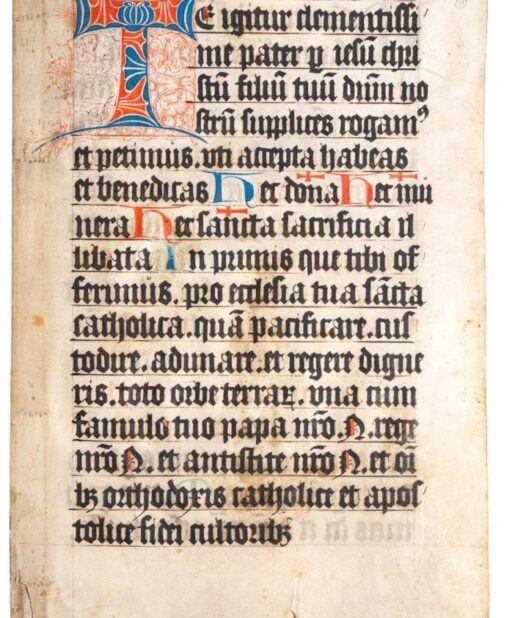

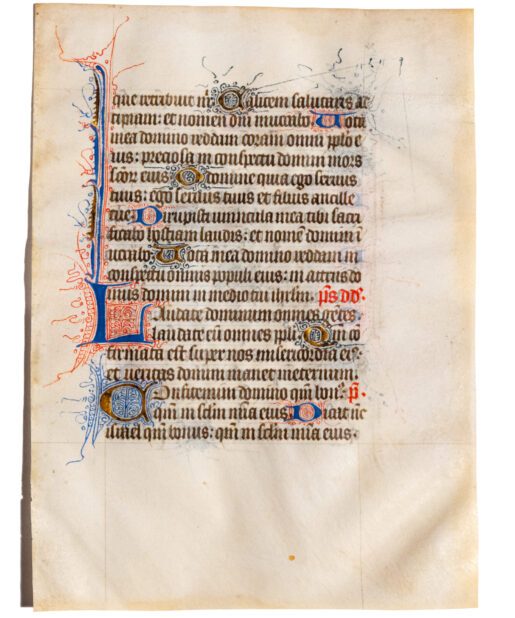

Beautiful two-column print. First and sole Latin incunabulum edition. Fly-leaves and first leaf with contemporary handwritten entries and erasures. First quire and last leaf a little restored. With a few manuscript marginalia and annotations. Occasional, partly restored tears in margins. Lightly browned and brown stained, increasingly waterstained above and specially towards the end, faint traces of mould in parts, some fingermarks and wormholes

Simon Fidati de Cassia (died 1348) was an Augustinian hermit and preacher in Perugia, Bologna, Siena, Florence and other northern Italian cities and was beatified by Pope Gregory XVI.

This incunable warrants particular attention for several compelling reasons:

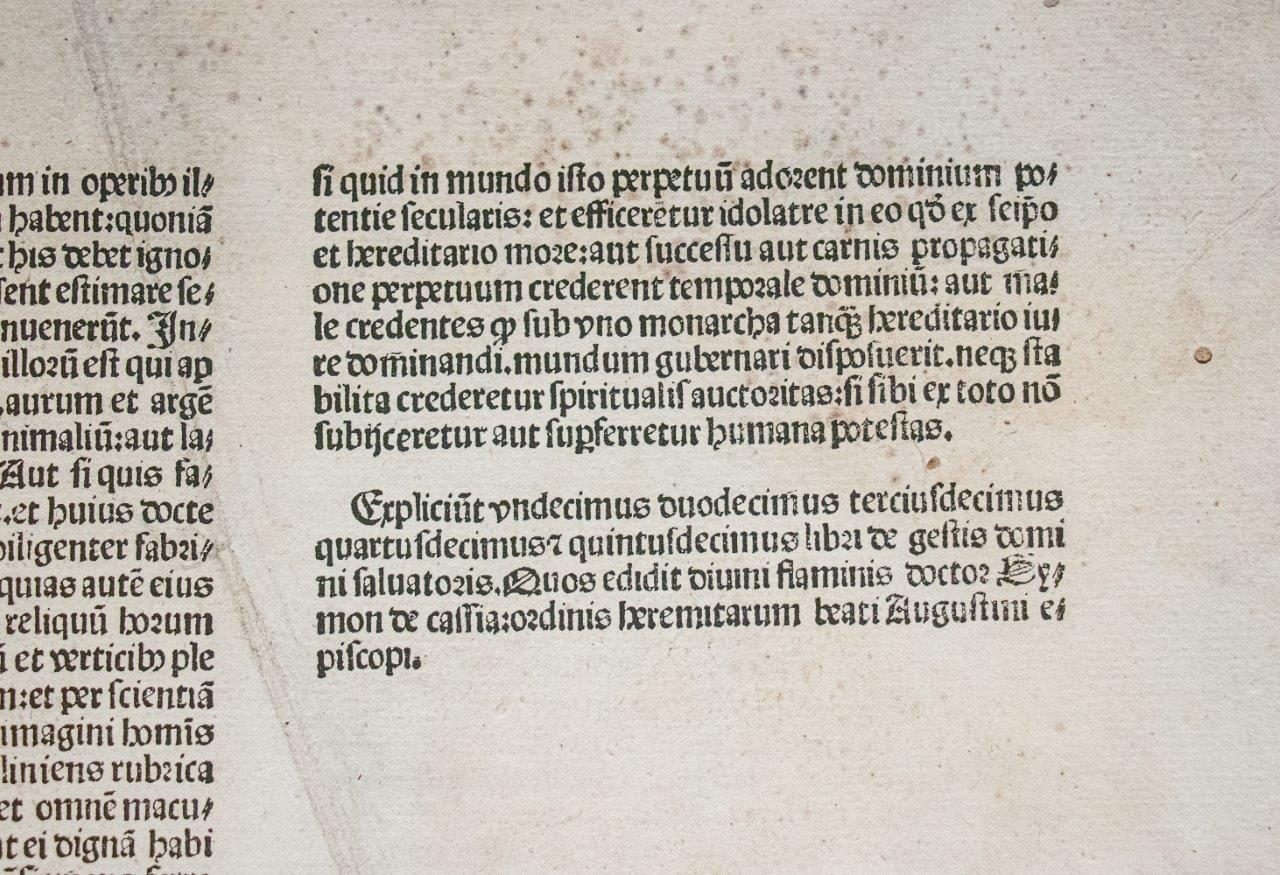

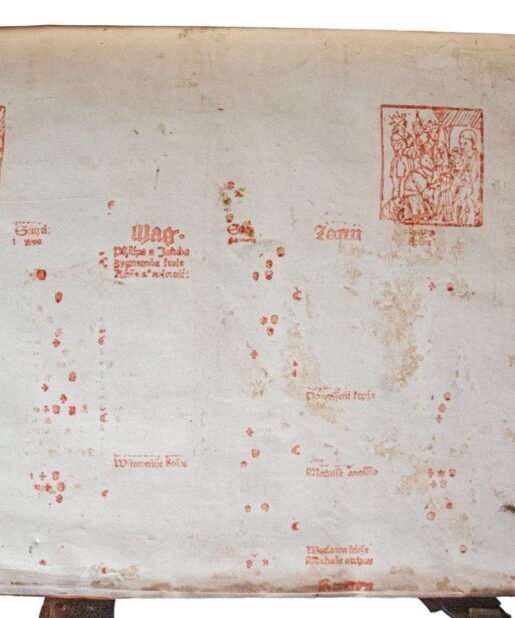

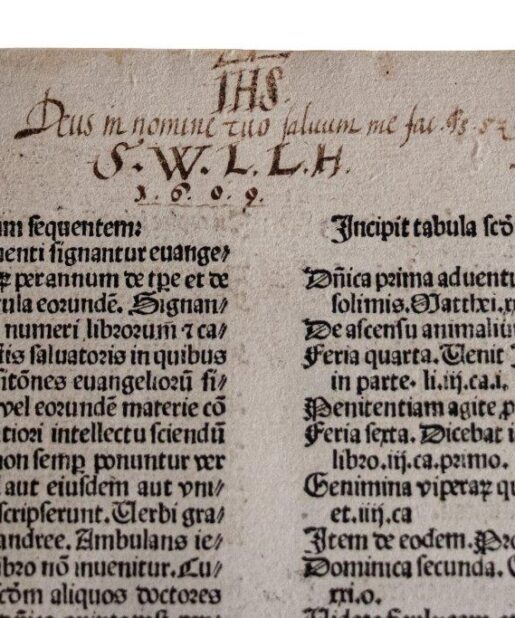

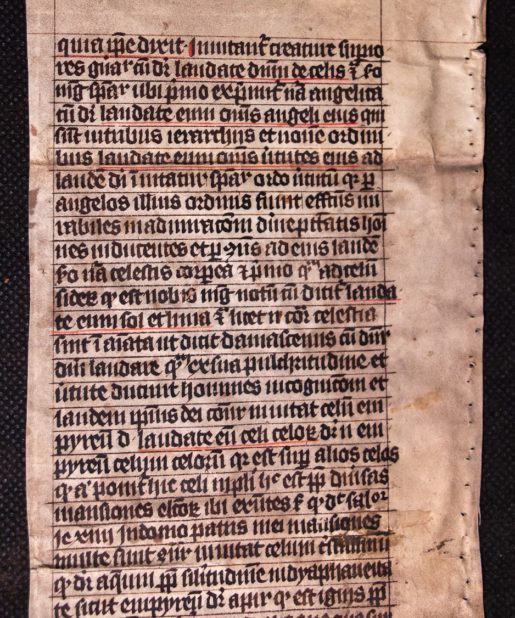

Firstly, it features front and rear endpapers made from waste sheets of a calendar printed in Czech, executed solely in red ink. This reveals an evident exploration of the optimal combination between red and black printing techniques. It is plausible that this calendar may have originated during the incunable period, thereby rendering it of immense significance for the history of printing in the Czech Republic. Such a remarkable aspect certainly calls for further scholarly investigation by specialists in the field. Our research indicates that Johannes Alakraw from Passau, who operated in Vimperk, produced the first Czech wall calendar for the year 1485, notably compiled by M. Laurentius of Rokycan, an astronomer at the University of Prague.

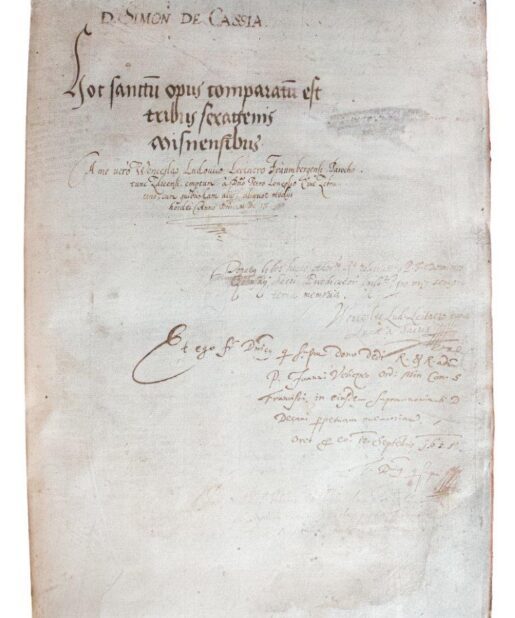

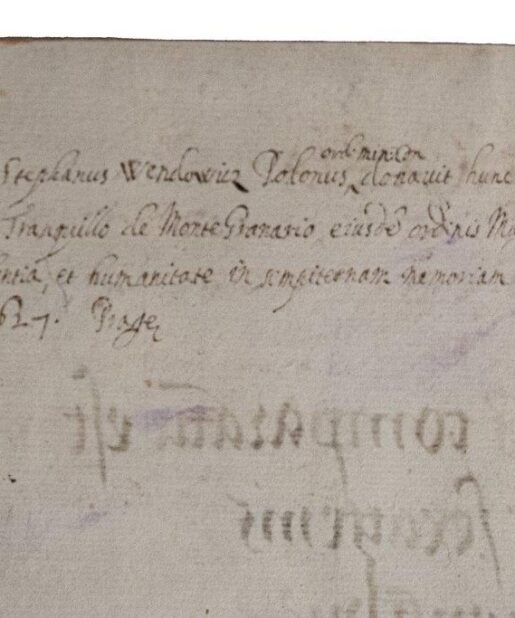

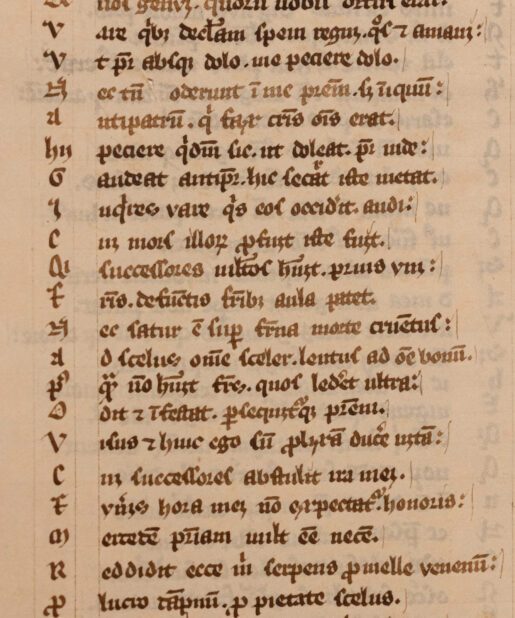

Secondly, a remarkable feature of this incunable lies on the reverse side of one of the calendar proofs, where an ancient manuscript in Old Czech is inscribed. Around 1400, Jan Hus introduced a written language based on the Prague dialect of his time, and this specimen, dating from the 15th century, exemplifies that linguistic evolution. Not only is it significant linguistically, but it also contains an incomplete recipe for a medicinal remedy aimed at treating kidney and bladder stones, likely used in the practices endorsed by Hildegard of Bingen. Regrettably, the first line or possibly the first two lines appear to be missing, likely recorded on a separate sheet.

The recipe mentions ingredients such as burnet-saxifrage, rose hips, and wild carrots, to be washed down with pea broth or white beer. Following this, it is recommended that the patient lie down in their clothes to facilitate healing. The final lines describe an alternative recipe in which “a radish is cut like a carrot,” pounded in a mortar, boiled in wine, and then consumed. Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) famously stated: “If anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract or in the (urinary) bladder of the human body mucus accumulates and hardens like a stone, then crush stonebreaker seeds in water and let this be drunk often after meals—never on an empty stomach!”

Only a few examples of Czech language texts from the medieval period focusing on medicinal topics have survived. One such manuscript from the mid-15th century is housed in the Czartoryski Library in Krakow, with the call number B 1497. This document is, therefore, an extraordinary find: a medicinal recipe in Old Czech, originating from the 15th century, which is of exceptional rarity and significance.

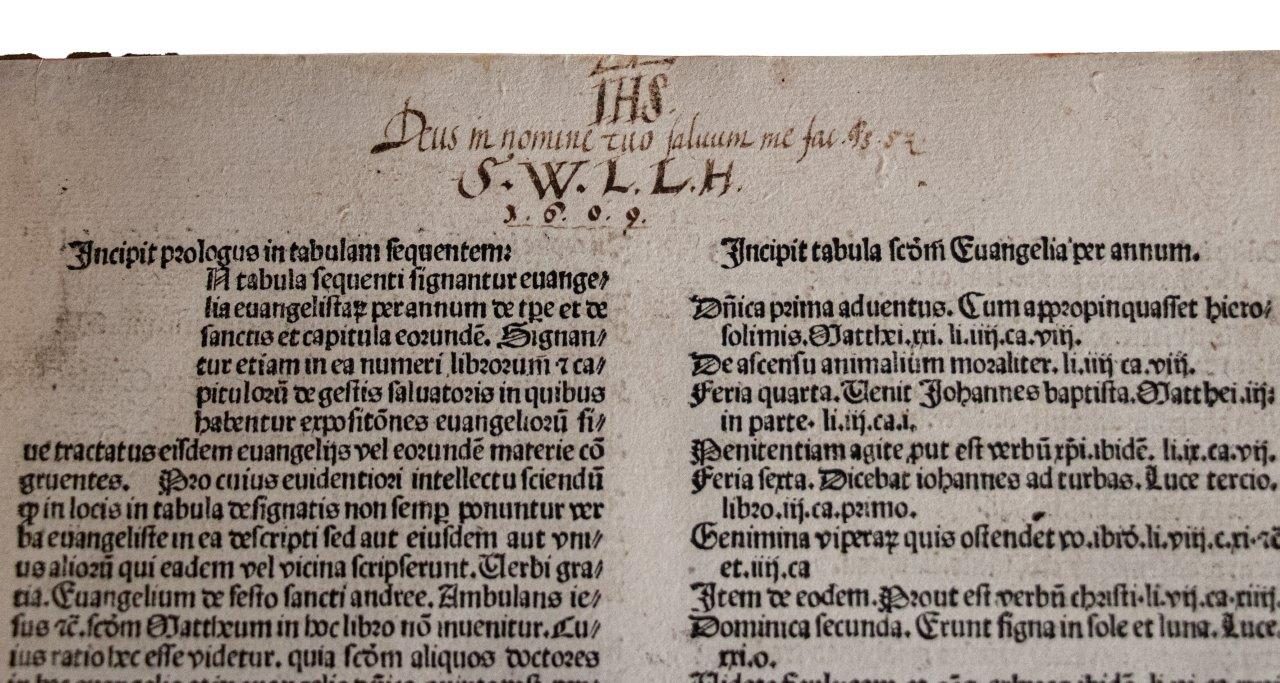

Additionally, the endpapers include many notes in an old hand, featuring phrases such as “Timor Dei vere ditat,” dated 1558, and a purchase note from a priest in Zdice, Bohemia, dated 1609. The first sheet bears an ownership note from 1609 and an erased ownership mark at the foot of the first column. These endpapers represent Czech printed versions of the German Aderlasskalender (blood-letting calendar) and are dated around 1500, making them some of the earliest examples of Czech printed blood-letting calendars known.

Towards the top and the end of the volume, there are increasingly noticeable water stains, with the first and last sheets somewhat restored. Mild worm damage is present, resulting in slight letter loss, alongside a few partially restored marginal tears. Marginalia and hand-written references appear throughout, with occasional slight browning.

The volume showcases a beautiful two-column print, bound in contemporary blind-stamped calf over wood with two metal clasps (somewhat restored). The endleaves have been renewed, although some wormholes remain, and the binding shows moderate rubbing and scuffing.

Johannes Alakraw was a notable printer in Passau, where in 1482 he printed a small Latin book (H 9128) with Benedikt Maier. In 1484, he printed two Latin texts (H 2013 and H 458) in Winterberg (Vimperk) in Bohemia, in addition to the oldest known Czech wall calendar.

Special thanks to Markéta Pytlíková, Head of The Department of Language Development at the Czech Language Institute, Czech Academy of Sciences, for her invaluable contributions to our understanding of this text.

Be the first to review “C15th Czech manuscript for a recipe in Old CZECH – Very early printed proof copy of an unknown calendar in CZECH – all in a 1484 edition of Simon de Cassia in contemporary binding.” Cancel reply

Product Enquiry

Related products

C14th -C16th manuscripts

A C14th cutting from a Noted Breviary with music on a 4-line stave arranged around a red clef line

C14th -C16th manuscripts

C14th -C16th manuscripts

C14th -C16th manuscripts

C14th -C16th manuscripts

Finely produced illuminated leaf from a French Psalter, c.1480

C14th -C16th manuscripts

An illuminated leaf from the Beauvais Missal, on vellum. [Northern France, c. 1310]

C14th -C16th manuscripts

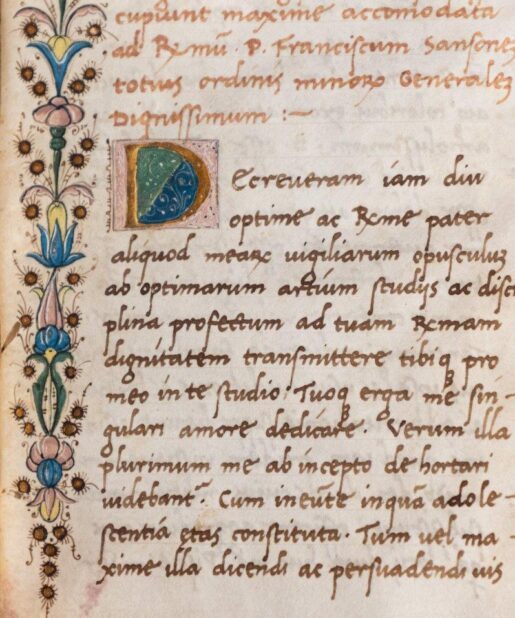

Unknown codex by humanist Bernardius Florentius, 1476, Florence, Italy

![An illuminated leaf from the Beauvais Missal, on vellum. [Northern France, c. 1310] An illuminated leaf from the Beauvais Missal, on vellum. [Northern France, c. 1310]](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/IMG_9687-515x618.jpg)

![An illuminated leaf from the Beauvais Missal, on vellum. [Northern France, c. 1310] An illuminated leaf from the Beauvais Missal, on vellum. [Northern France, c. 1310]](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/IMG_9683-515x618.jpg)

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.