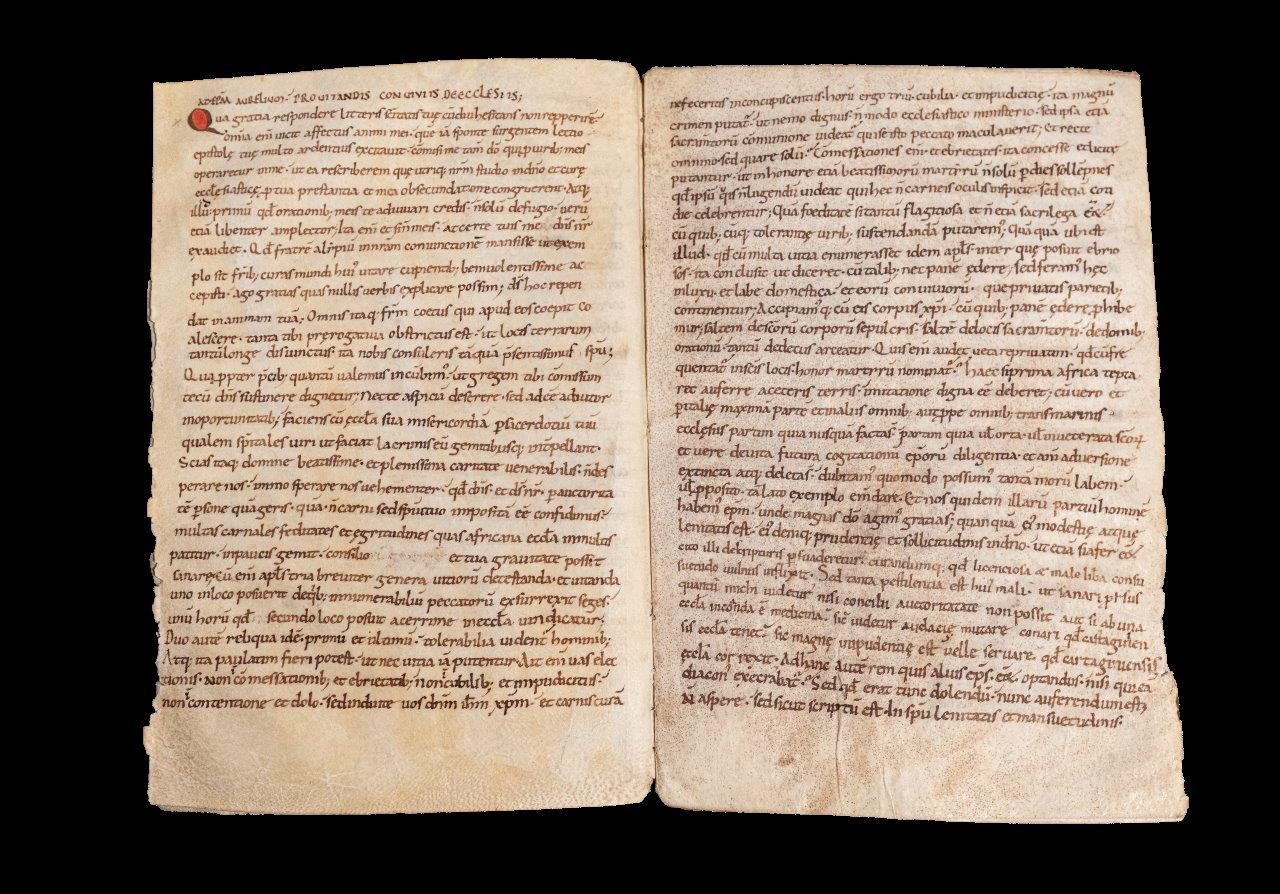

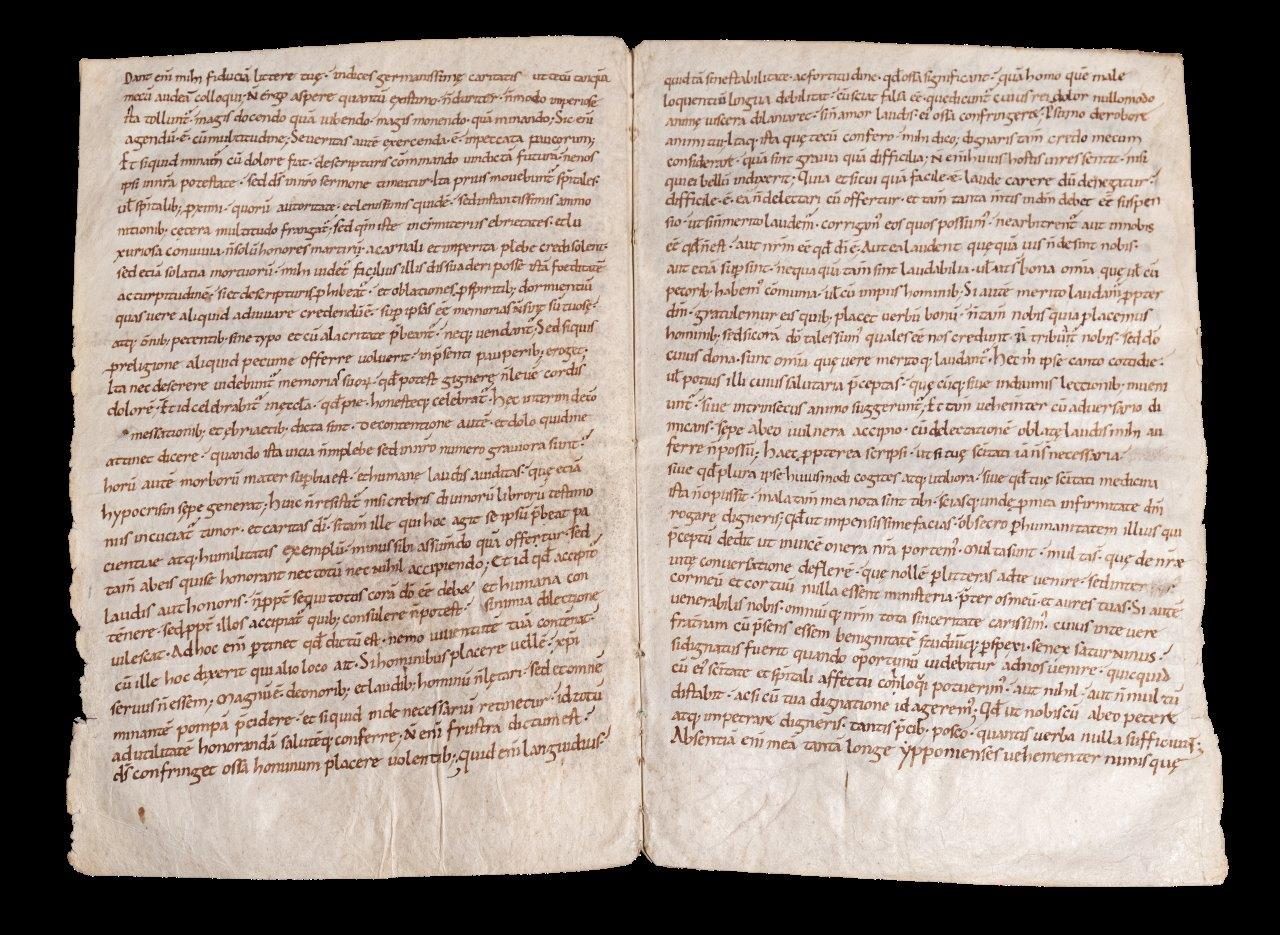

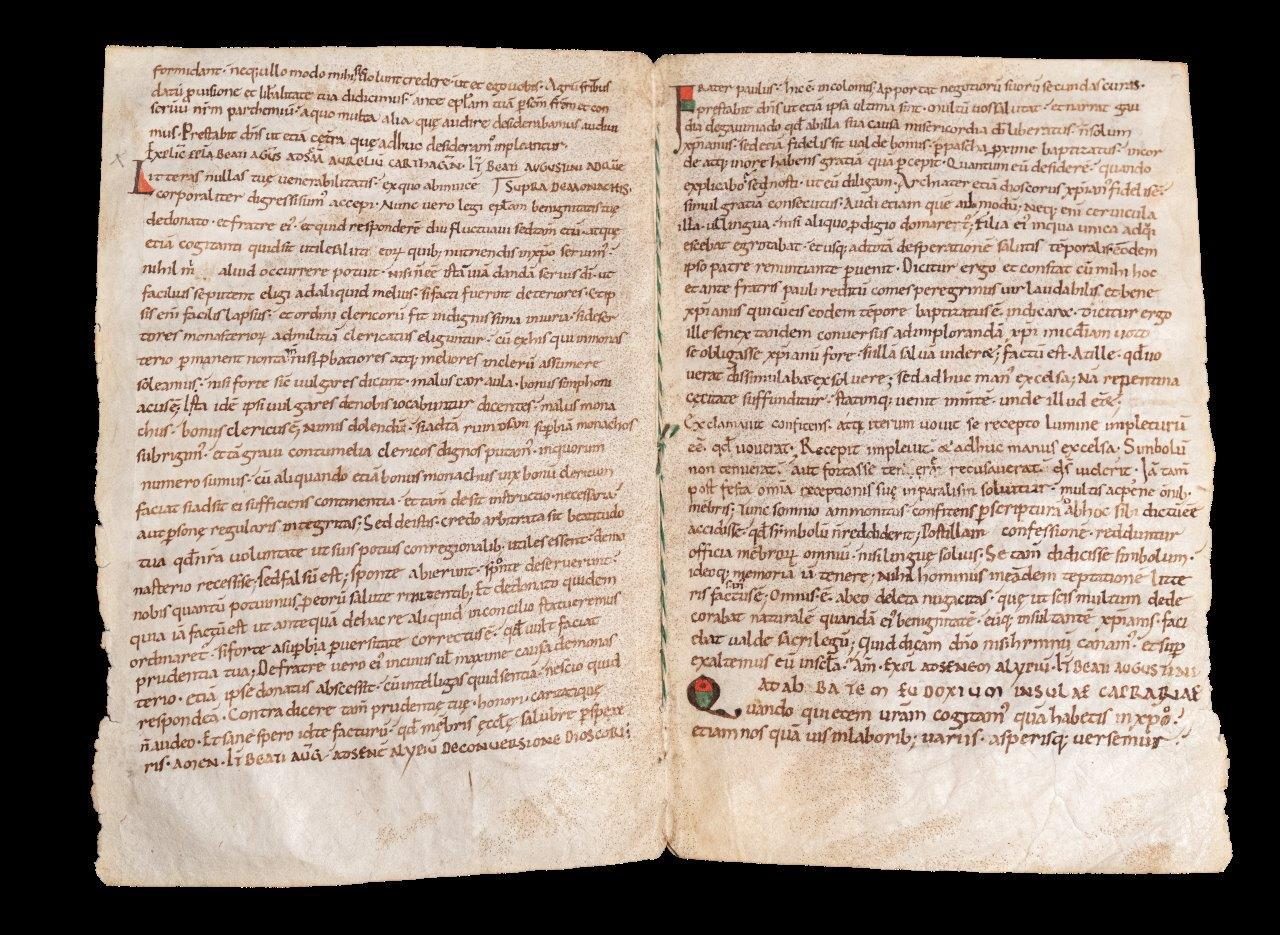

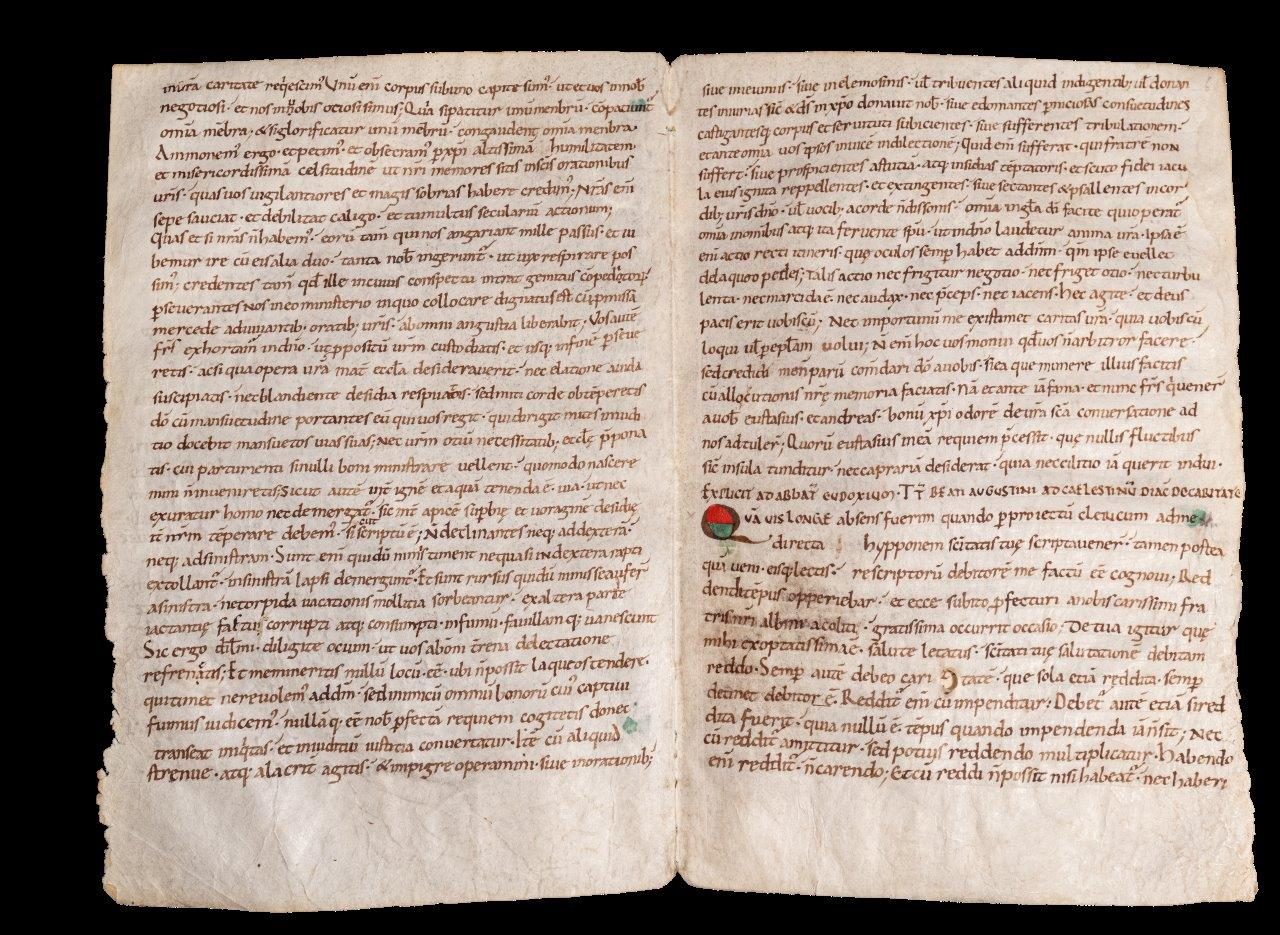

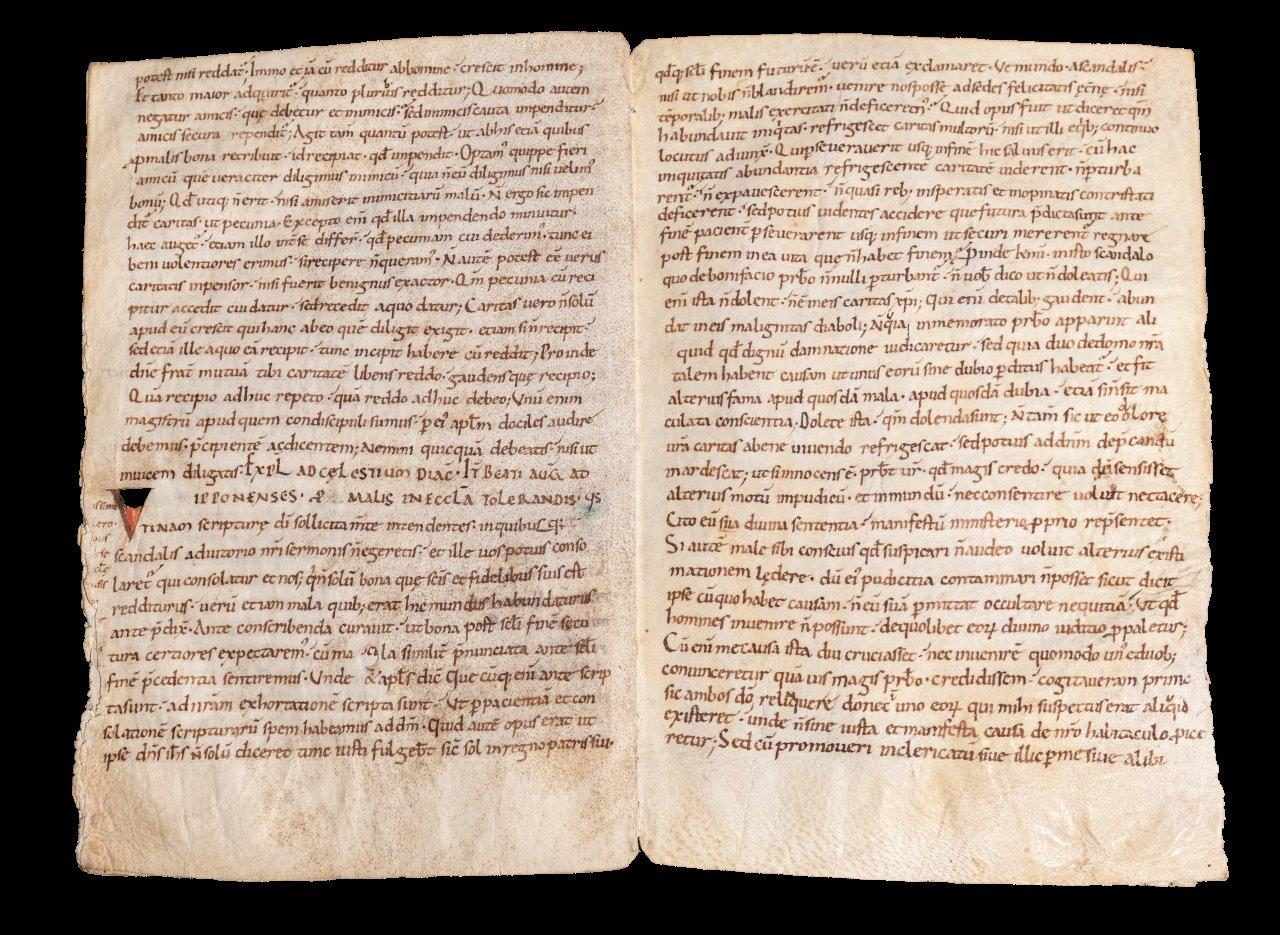

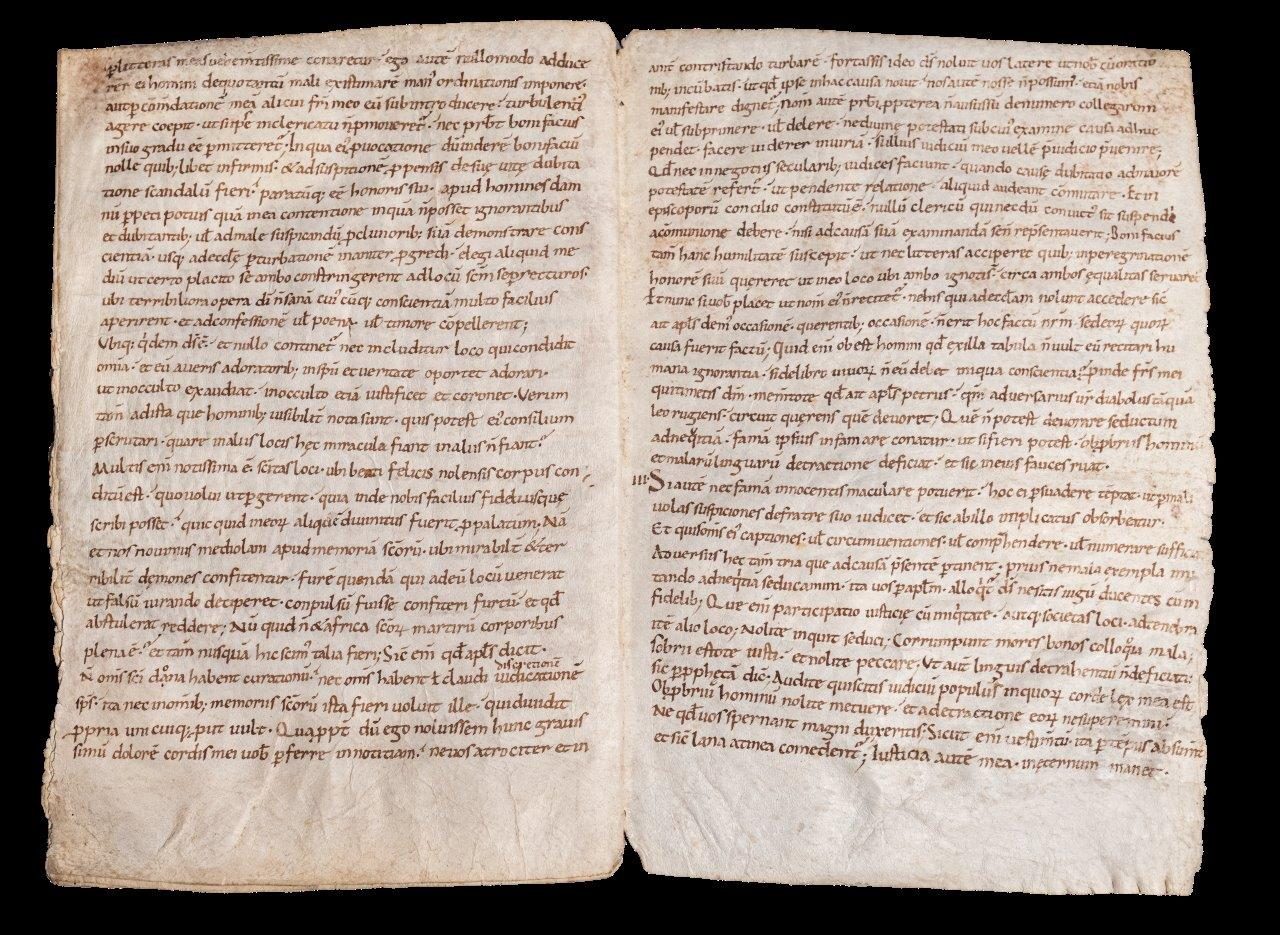

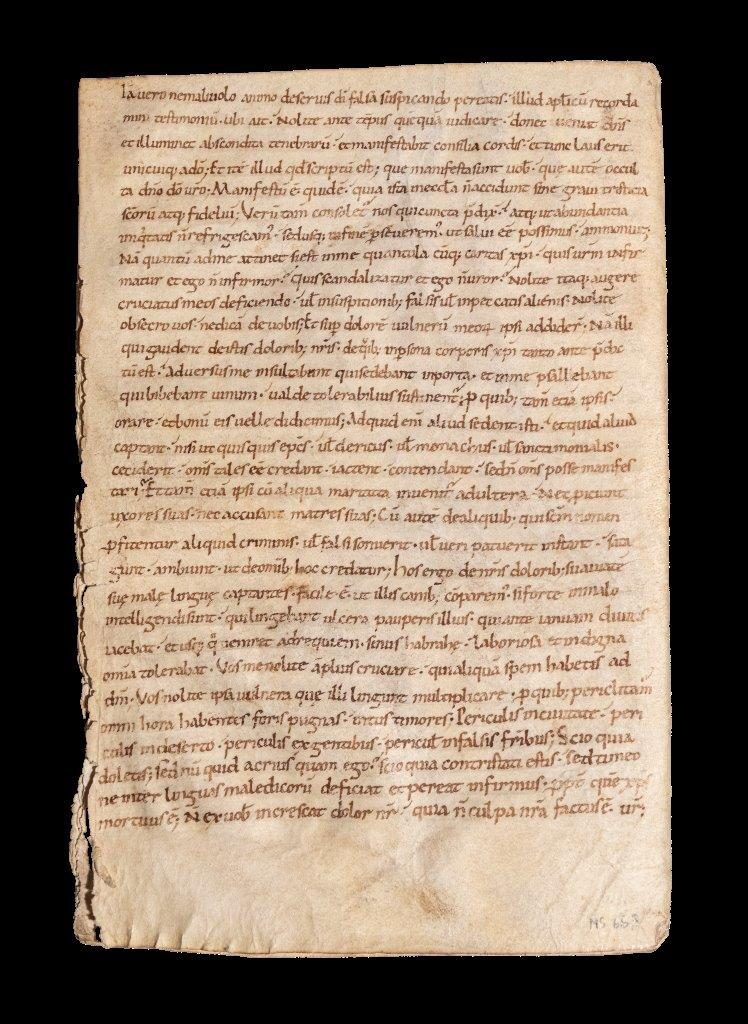

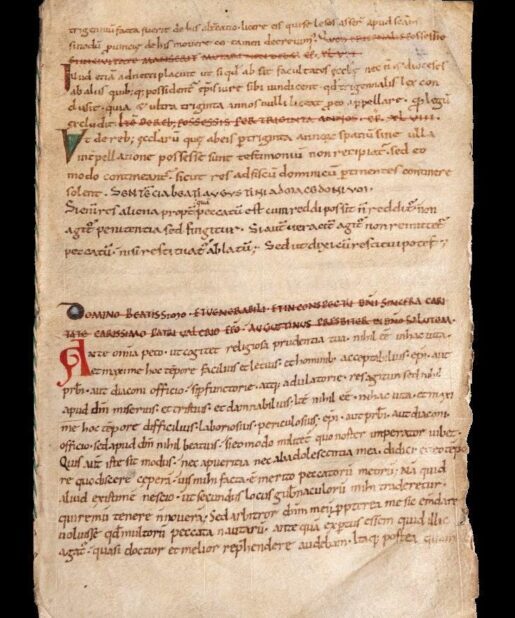

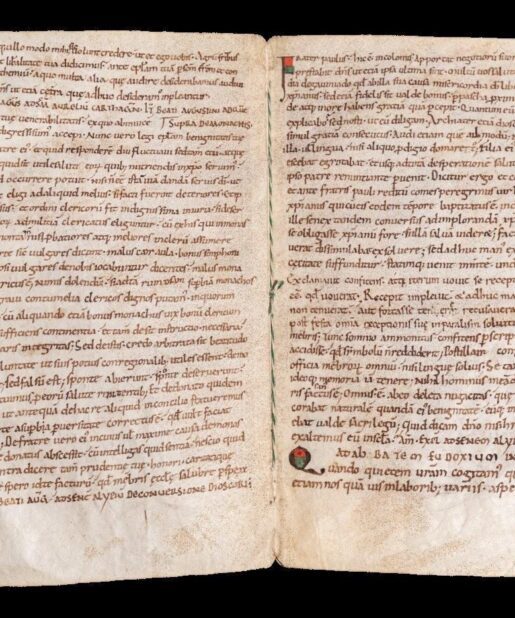

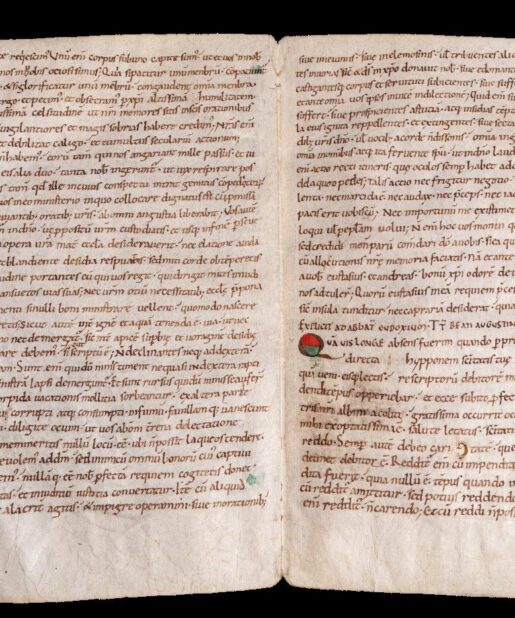

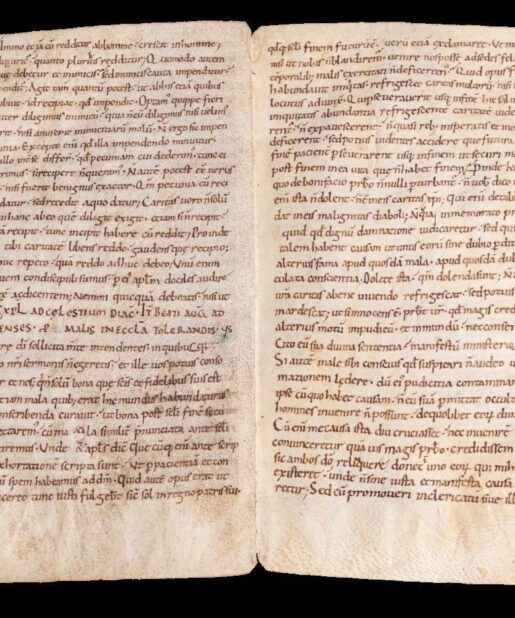

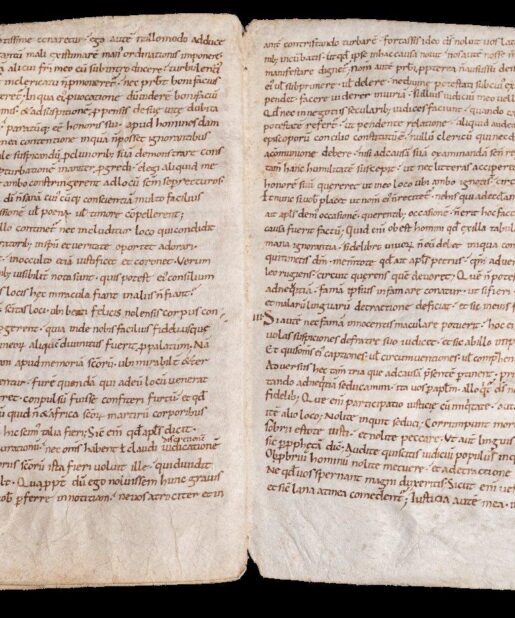

Complete gathering of Augustine’s Letters, France, early C11th

£15,000.00

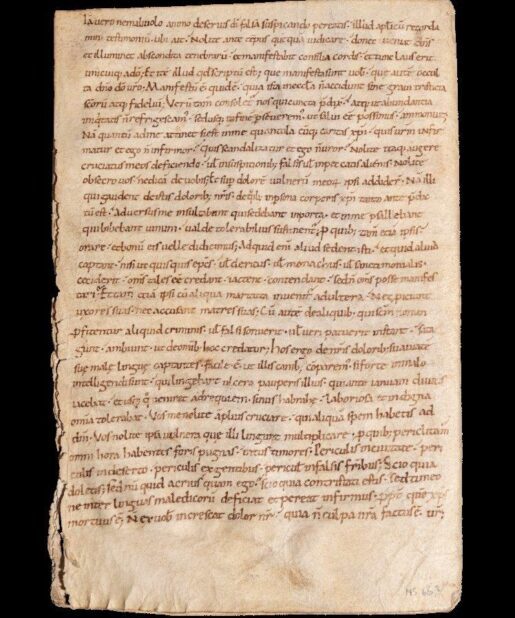

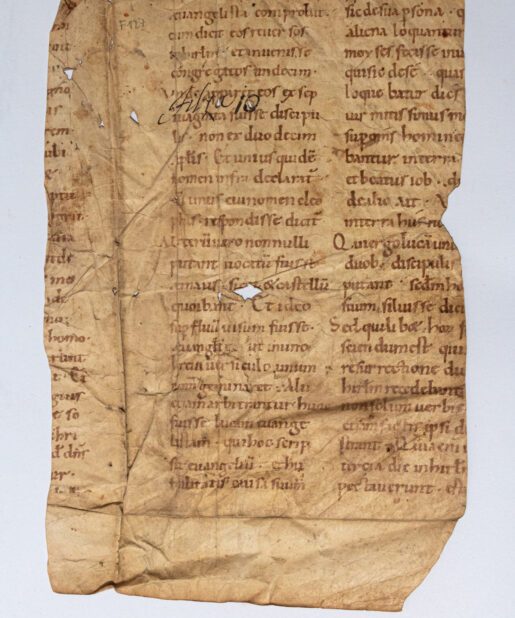

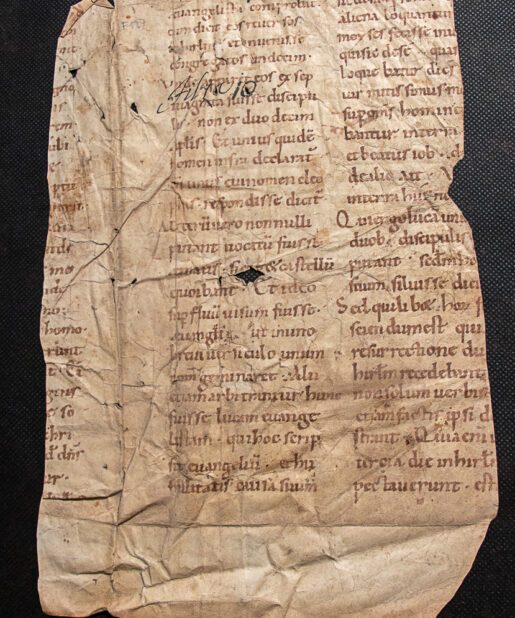

Augustine, Epistulae, in Latin, single gathering from a fine Romanesque manuscript on parchment; France (northern France, perhaps Loire valley), eleventh century .

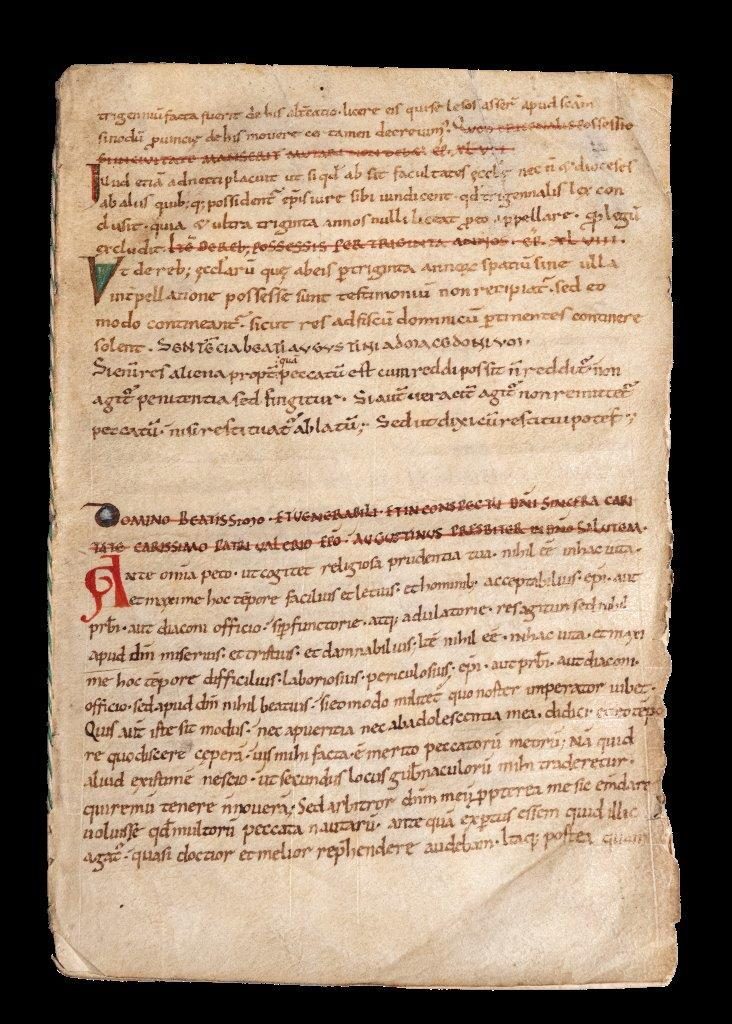

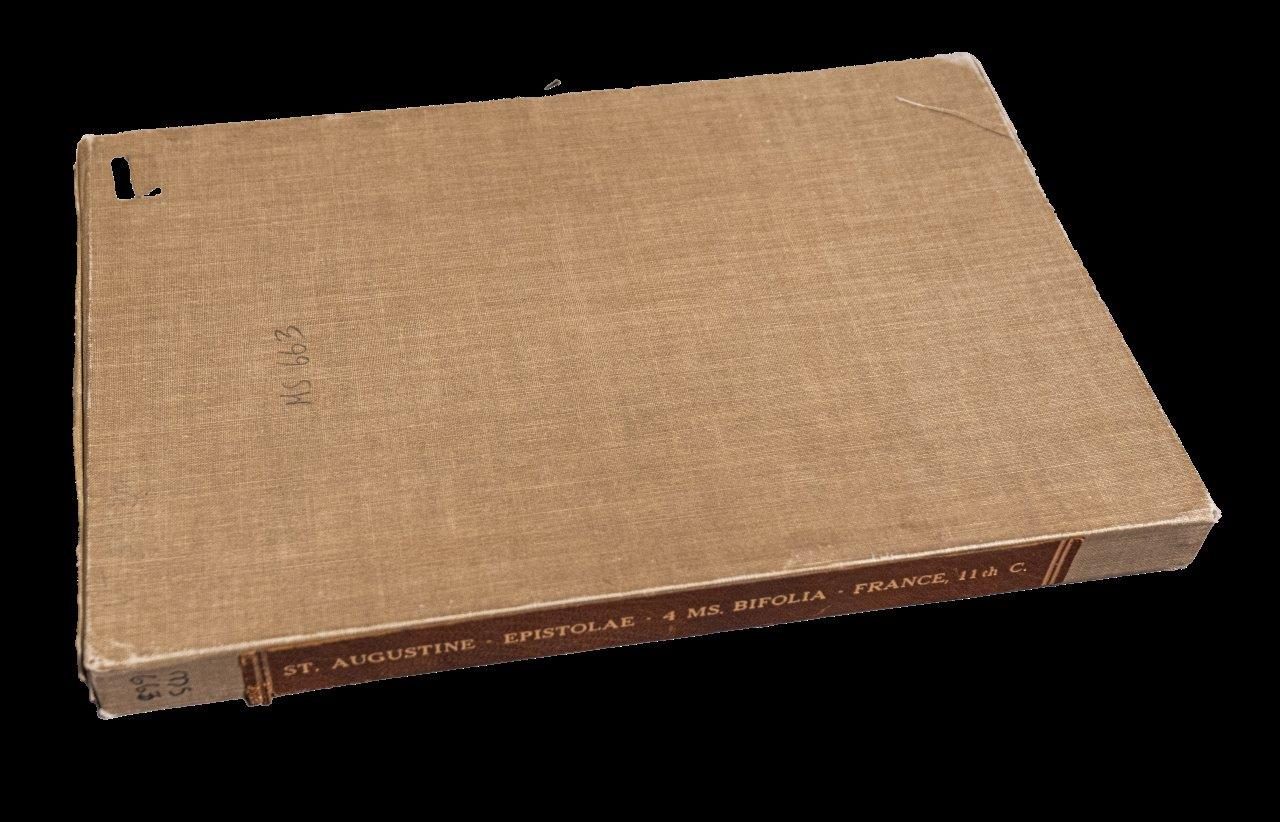

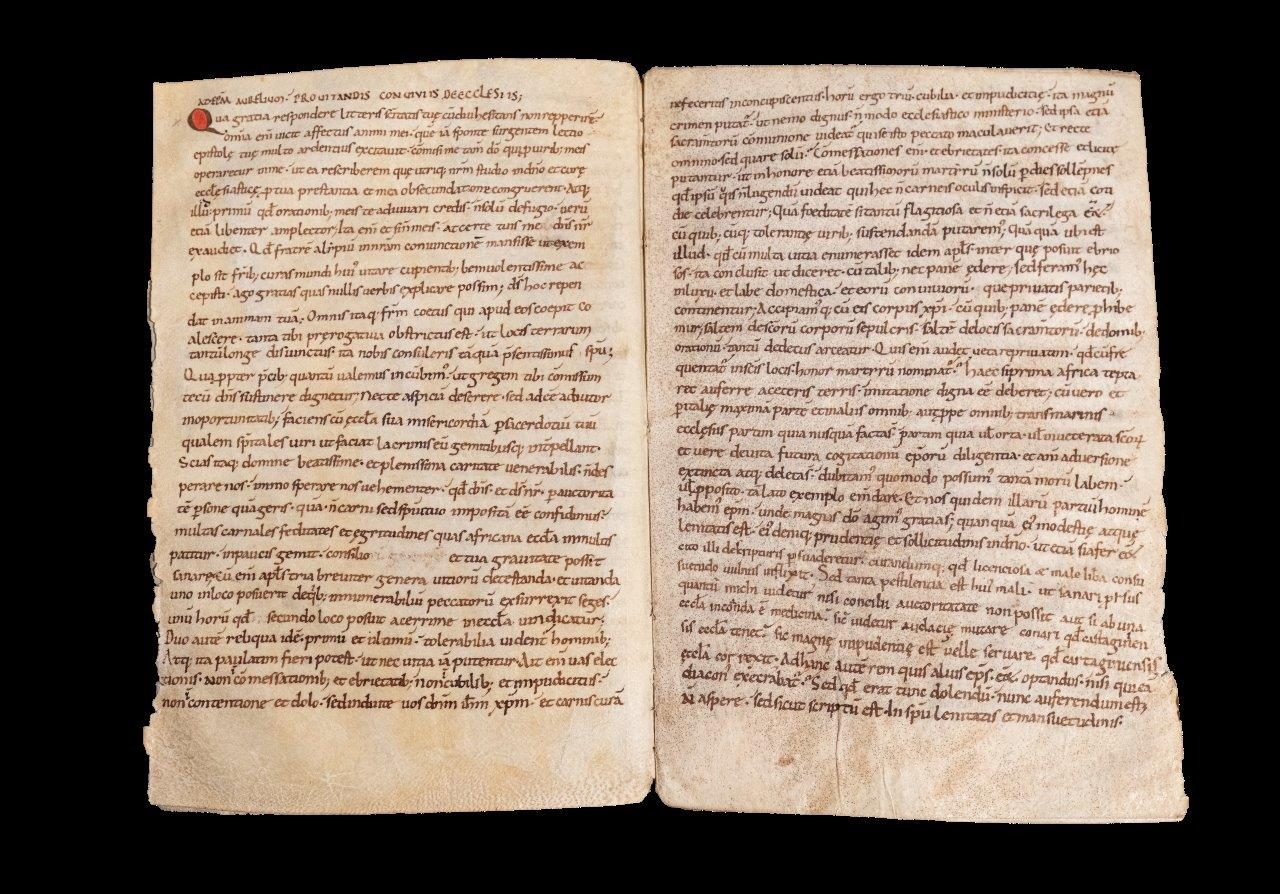

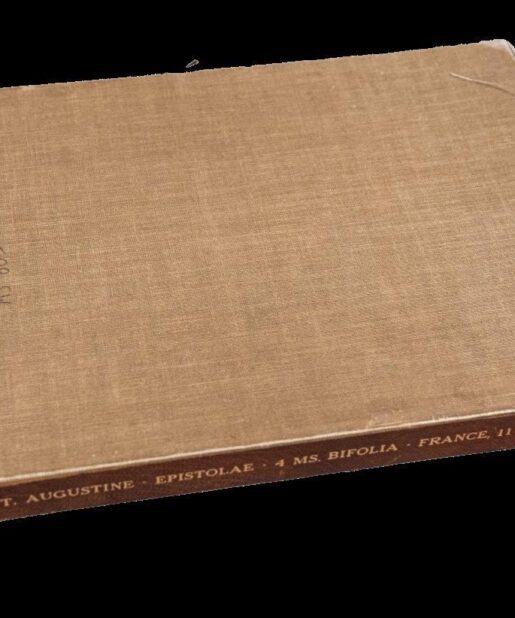

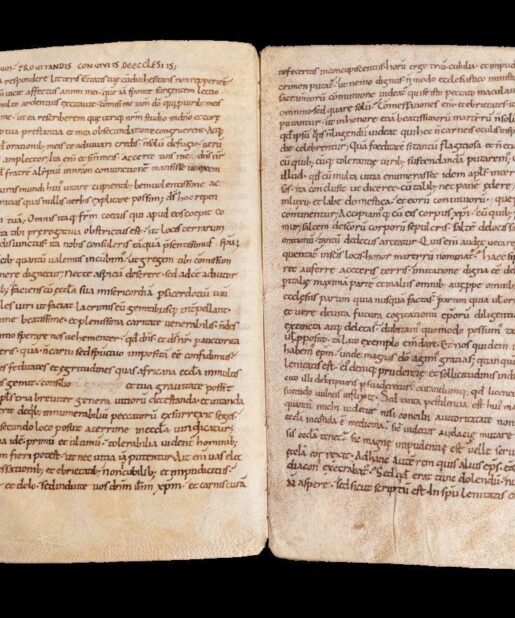

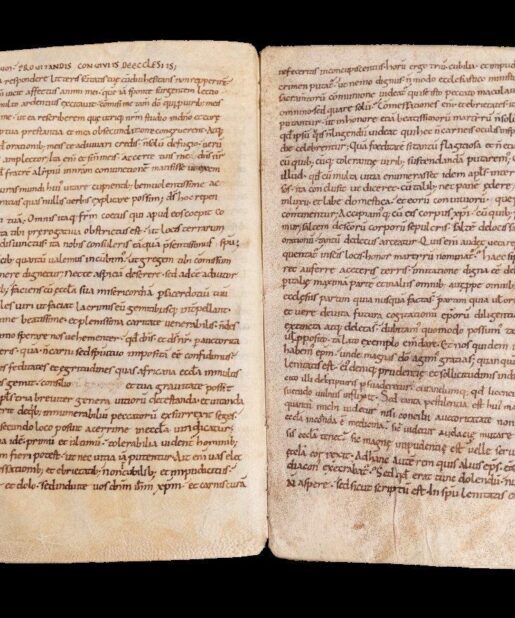

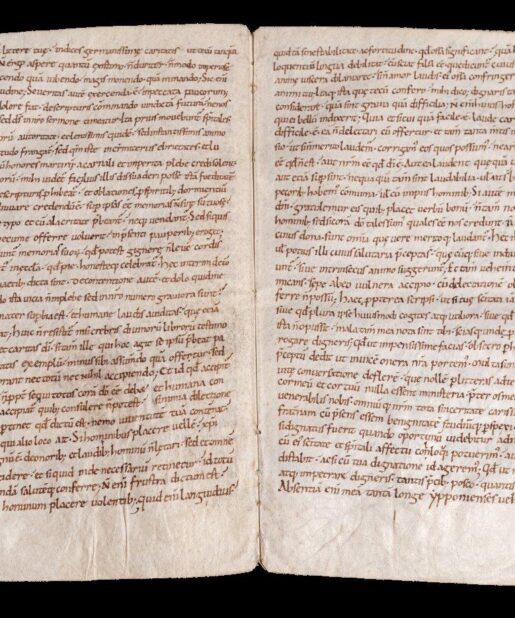

Single gathering of 8 leaves, with single column of 29-31 lines in a good Romanesque hand that leans slightly to the right, with a tongued ‘e’, pronounced wedging to ascenders, and very few abbreviations, headings in ornamental capitals whose form shows their strong debt to Carolingian minuscule, these lined through in red penwork, 2-line initials in simple brown, blue or red, these infilled with dark teal green or red wash (sometimes together in compartments), or occasionally dark blue on own, the gathering stitched with later coloured thread, one small tear to edge repaired, fol. 6 trimmed with losses to marginalia, damage to outer upright edges of leaves on some leaves (perhaps rodent damage), slightly cockled overall, else excellent condition, 250 x 160mm.; in fitted slipcase within cloth-covered box

Provenance:

1. Written and decorated in northern France in the early eleventh century, perhaps in the Loire valley, and doubtless for a monastic or cathedral centre.

2. Maggs Bros. of London, cat. 1110 (1990), no. 1.3. Schøyen Collection, London and Oslo, their MS 663, acquired from Maggs in June 1990.

Text and script:

While the contributions of the Confessions and City of God of St. Augustine of Hippo (354-422) to the early Church are well known, the impact of his letters is often overlooked. Some 254 letters of his survive, written to a variety of correspondents over forty years from the 380s to his death in 430. Augustine greatly valued this method of conversation with those geographically distant from him, and in fact some correspondents such as Jerome he would never meet in person and knew only through their letters. These letters were diligently collected by him, but not included in his listing of his own works, the Retractationes, as they were most probably to be the subject of another catalogue, which unfortunately he died before he could begin. Possidius, his friend and a fellow bishop, listed them on Augustine’s death alongside his unlisted sermons, in the Indiculum, most probably working through the documents sorted into piles by Augustine himself before his death. They are intensely personal documents, and it is through them that we come closest to meeting Augustine the man, rather than the polished author. They were essential reading in religious communities throughout medieval Europe, but very few manuscripts contain anything like a comprehensive corpus, and all known manuscripts before the thirteenth century divide into three main groups, with the order of the letters included here indicating that it follows the tradition represented by BnF. ms 12226 (Corbie, ninth century) and 12193 (Loire valley, c. 900).

The letters here are: (i) letter to Valerius, bishop of Hippo, probably written soon after Augustine was ordained to become Valerius’ assistant (and eventual successor as bishop), in this letter Augustine confesses to his unworthiness for this course, and how his pride further hampered him (fol. 1r; J.P. Migne, Patrologia Latina 33, no. 21); (ii) letter to Aurelius, Deacon and later bishop of Carthage, Augustine’s closest friend, written c. 392 and on the subject of Aurelius’ attacking of sin in the north African Church, including drunkenness during the veneration of saints’ tombs (fol. 2v; no. 22); (iii) letter to the same Aurelius, written in 401, discussing the heresy of the Donatists (fol. 4v; Migne, no. 60); (iv) letter to Alypsius, bishop of Tagaste, an old friend, written in 428-429, and relating the miracle of Dioscurus’ conversion and his twice reneging of that religious oath (fol. 5r; Migne, no. 227); (v) letter to Eudoxius, abbot of a monastery on an island between Corsica and Tuscany, written in 398 (fol. 5r; Migne, no. 48); (vi) letter to Celestine, bishop of Rome, written c. 418 when Celestine was still a deacon (fol. 6r; Migne, no. 192); (vii) letter to the inhabitants of Augustinus’ see of Hippo, wants ending (fol. 6v; Migne, no. 78). The angularity of the script and its continued use of numerous Carolingian letterforms is characteristic of French hands in the eleventh century, and perhaps even those of more provincial centres, such as the Loire valley (cf. Tours, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 924, a copy of Terence produced in the Loire Valley in the first quarter of the twelfth century: W. Cahn, Romanesque Manuscripts in the Twelfth Century, 1996, no. 11). Similarly, the use of rich colours to infill initials, such as the teal green here, probably points to Carolingian models (cf. the Histories of Pompey Trogue, made in Corbie c. 800, for this common style: reproduced in Trésor carolingiens, 2007, no. 25), and the scribe and decorator of the present leaves probably followed a now lost Carolingian exemplar carrying over parts of the script and decoration.

Be the first to review “Complete gathering of Augustine’s Letters, France, early C11th” Cancel reply

Product Enquiry

Related products

C12th - C13th manuscripts

C12th - C13th manuscripts

Leaf of Passionale in Latin [Italy, 12th century, first half] Lives of St Felicity and St Clement

Illuminations

![Two half-leaves from a Sacramentary, in Latin, sumptuously illuminated manuscript on vellum [Germany, late 11th century or early 12th century] Two half-leaves from a Sacramentary, in Latin, sumptuously illuminated manuscript on vellum [Germany, late 11th century or early 12th century]](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_0268-2-515x385.jpg)

![Two half-leaves from a Sacramentary, in Latin, sumptuously illuminated manuscript on vellum [Germany, late 11th century or early 12th century] Two half-leaves from a Sacramentary, in Latin, sumptuously illuminated manuscript on vellum [Germany, late 11th century or early 12th century]](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IMG_0269-515x618.jpg)

![Saints Peter and Paul, in an illuminated historiated initial ‘N’, cut from a Gradual in Latin on parchment [Italy (Florence); 15th century (c.1470s)] Saints Peter and Paul, in an illuminated historiated initial ‘N’, cut from a Gradual in Latin on parchment [Italy (Florence); 15th century (c.1470s)]](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/IMG_6782-515x618.jpg)

![Saints Peter and Paul, in an illuminated historiated initial ‘N’, cut from a Gradual in Latin on parchment [Italy (Florence); 15th century (c.1470s)] Saints Peter and Paul, in an illuminated historiated initial ‘N’, cut from a Gradual in Latin on parchment [Italy (Florence); 15th century (c.1470s)]](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/IMG_6781-515x618.jpg)

![Fragmentary leaf from Chromatius of Aquileia, parts of sermons XIX–XX, probably from a Homiliary, in Latin, on vellum [Germany, 10th century] Fragmentary leaf from Chromatius of Aquileia, parts of sermons XIX–XX, probably from a Homiliary, in Latin, on vellum [Germany, 10th century]](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/IMG_1178-515x618.jpg)

![Fragmentary leaf from Chromatius of Aquileia, parts of sermons XIX–XX, probably from a Homiliary, in Latin, on vellum [Germany, 10th century] Fragmentary leaf from Chromatius of Aquileia, parts of sermons XIX–XX, probably from a Homiliary, in Latin, on vellum [Germany, 10th century]](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/IMG_1177-515x618.jpg)

![Commentary on Aristotle, Categoriae, and the same authors translation of Perihermenias BOETHIUS [MS] C.13th Commentary on Aristotle, Categoriae, and the same authors translation of Perihermenias BOETHIUS [MS] C.13th](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/IMG_8383-515x618.jpg)

![Commentary on Aristotle, Categoriae, and the same authors translation of Perihermenias BOETHIUS [MS] C.13th Commentary on Aristotle, Categoriae, and the same authors translation of Perihermenias BOETHIUS [MS] C.13th](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/IMG_8379-515x618.jpg)

![Leaf of Passionale in Latin [Italy, 12th century, first half] Lives of St Felicity and St Clement Leaf of Passionale in Latin [Italy, 12th century, first half] Lives of St Felicity and St Clement](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/IMG_0696-515x618.jpg)

![A single leaf; Augustine’s Enarrationes in Psalmos, for Psalm 41:6-8 [manuscript] A single leaf; Augustine’s Enarrationes in Psalmos, for Psalm 41:6-8 [manuscript]](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/IMG_2115-scaled-515x618.jpg)

![A single leaf; Augustine’s Enarrationes in Psalmos, for Psalm 41:6-8 [manuscript] A single leaf; Augustine’s Enarrationes in Psalmos, for Psalm 41:6-8 [manuscript]](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/IMG_2112-scaled-515x618.jpg)

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.