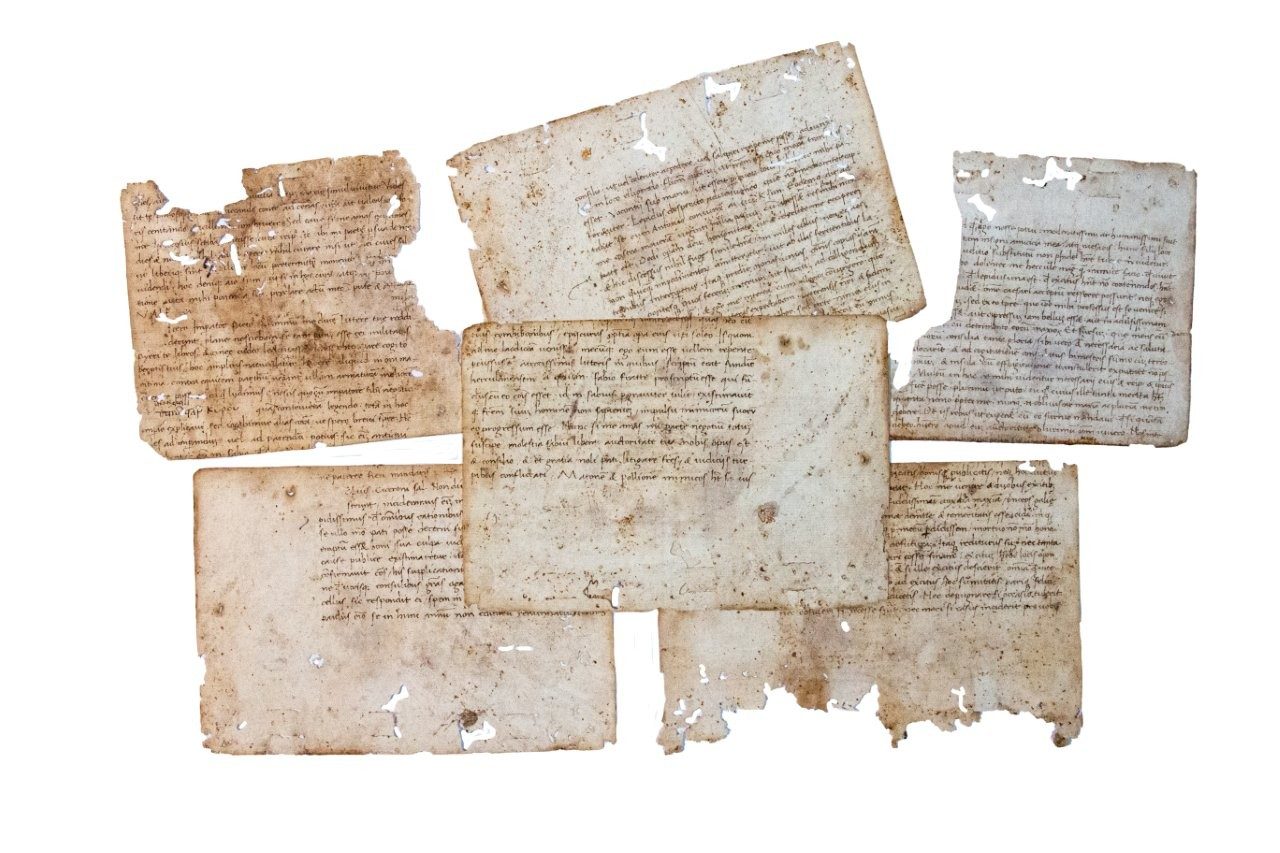

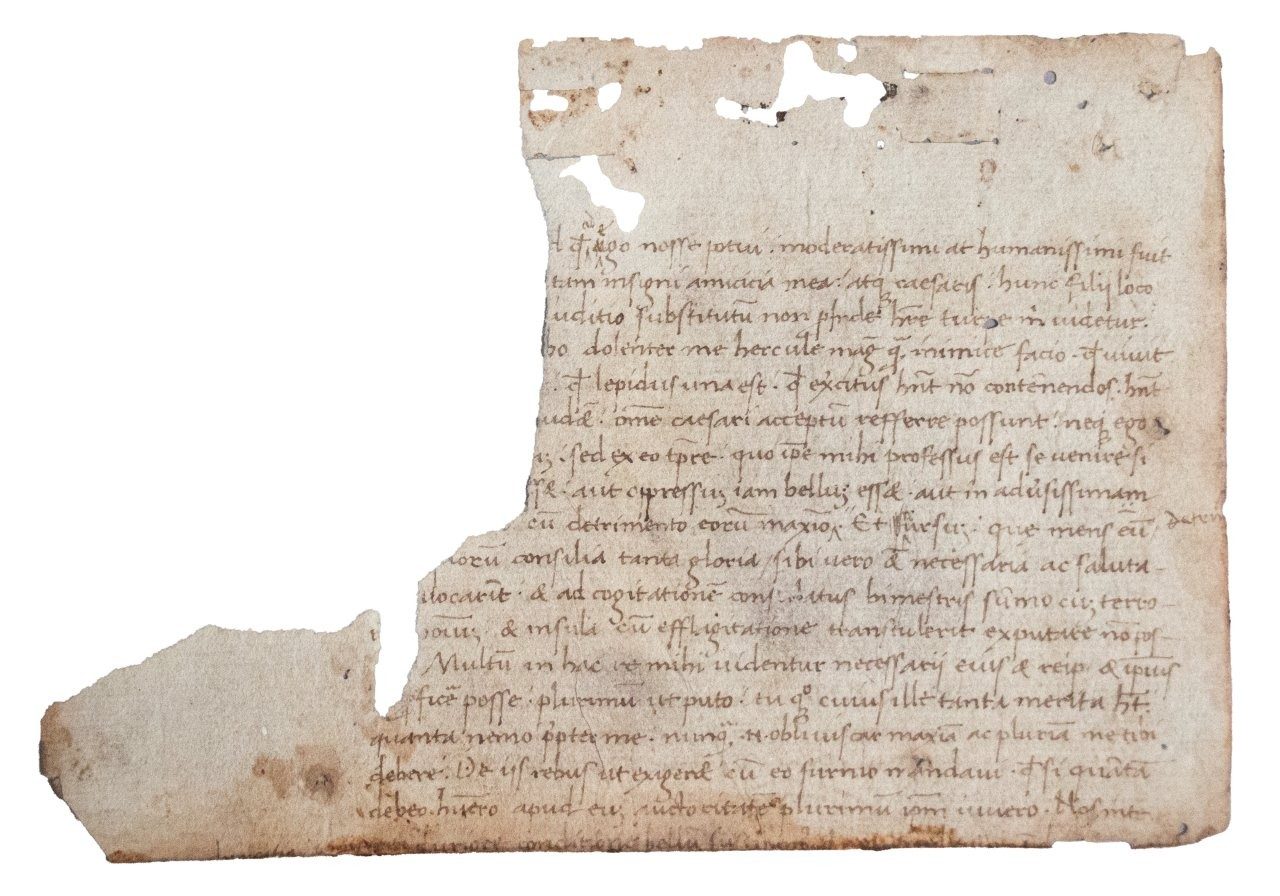

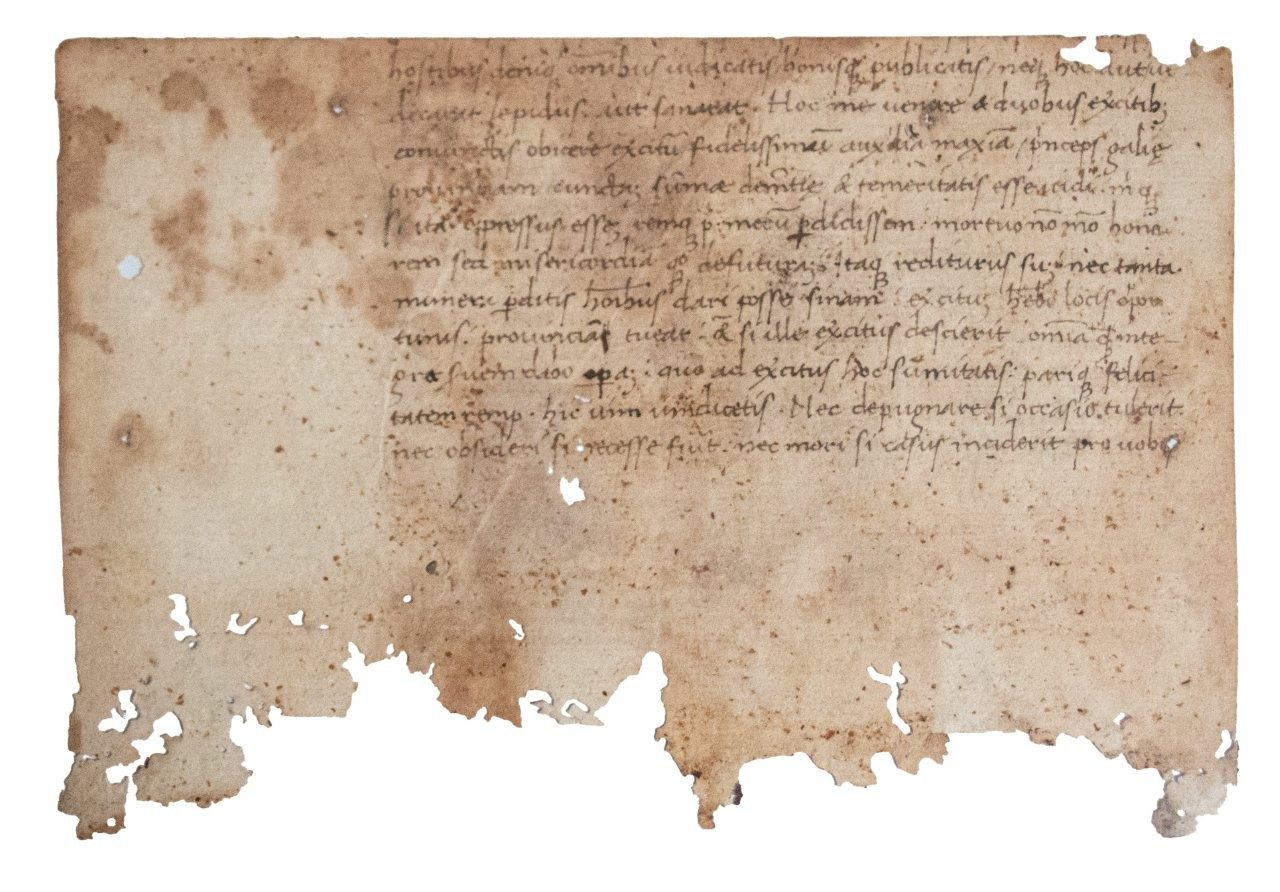

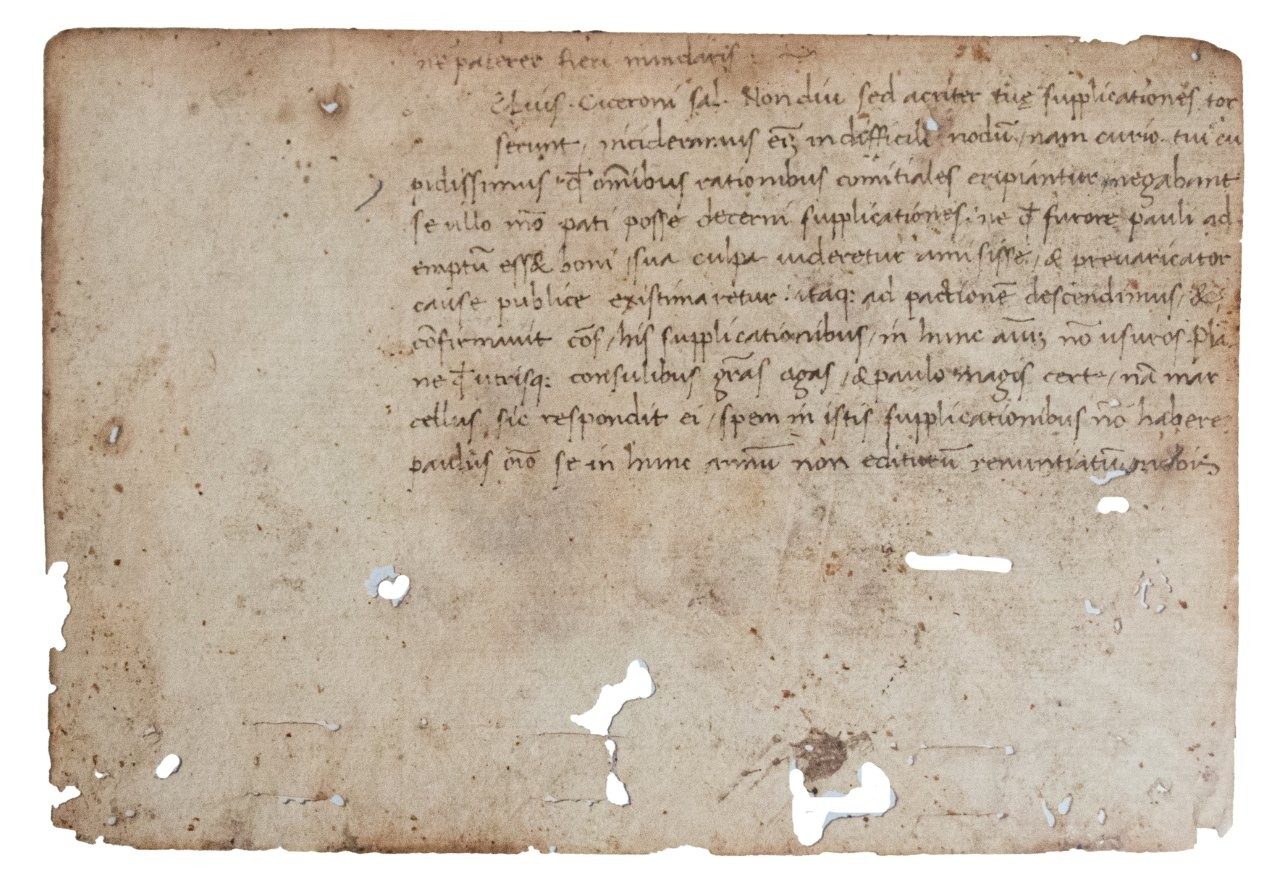

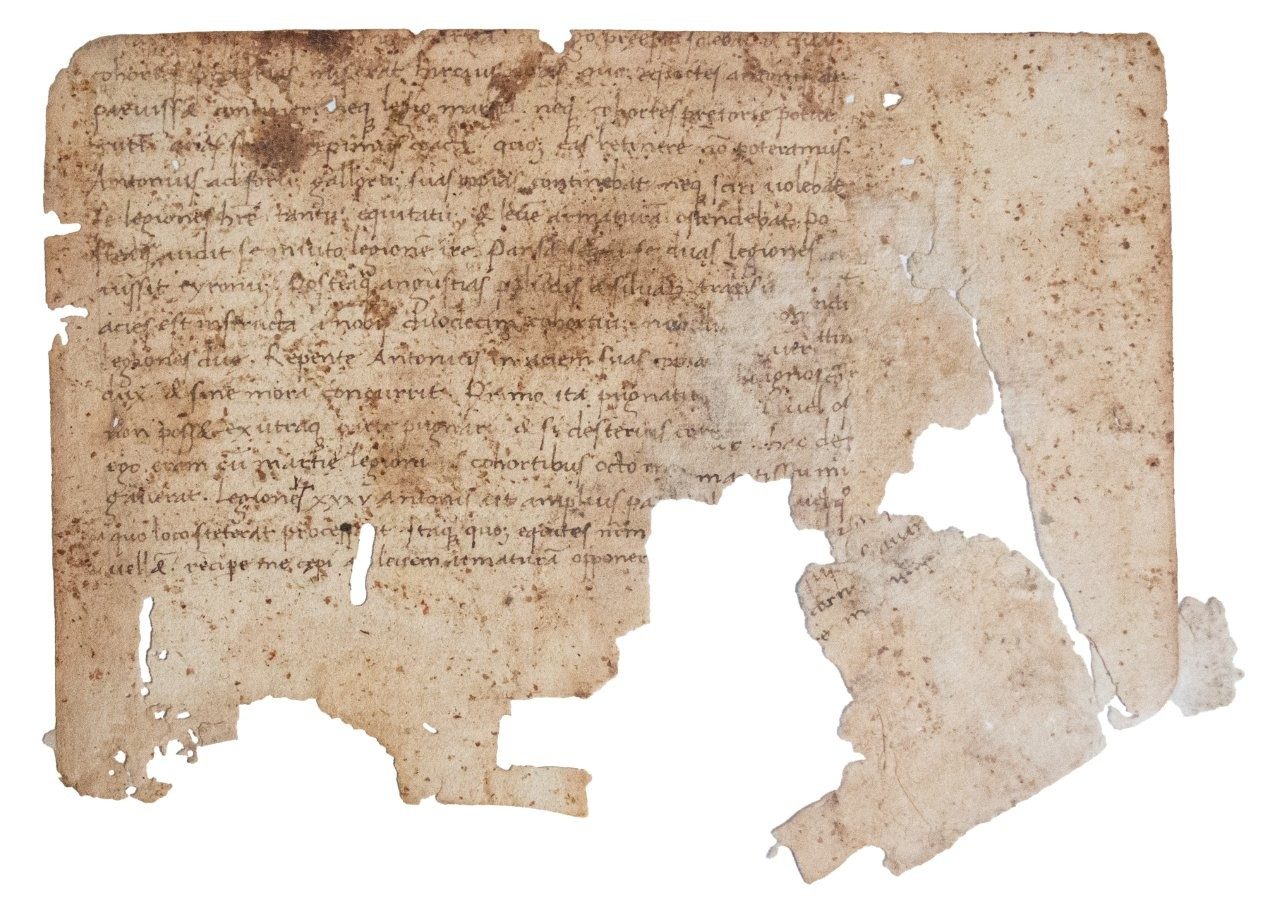

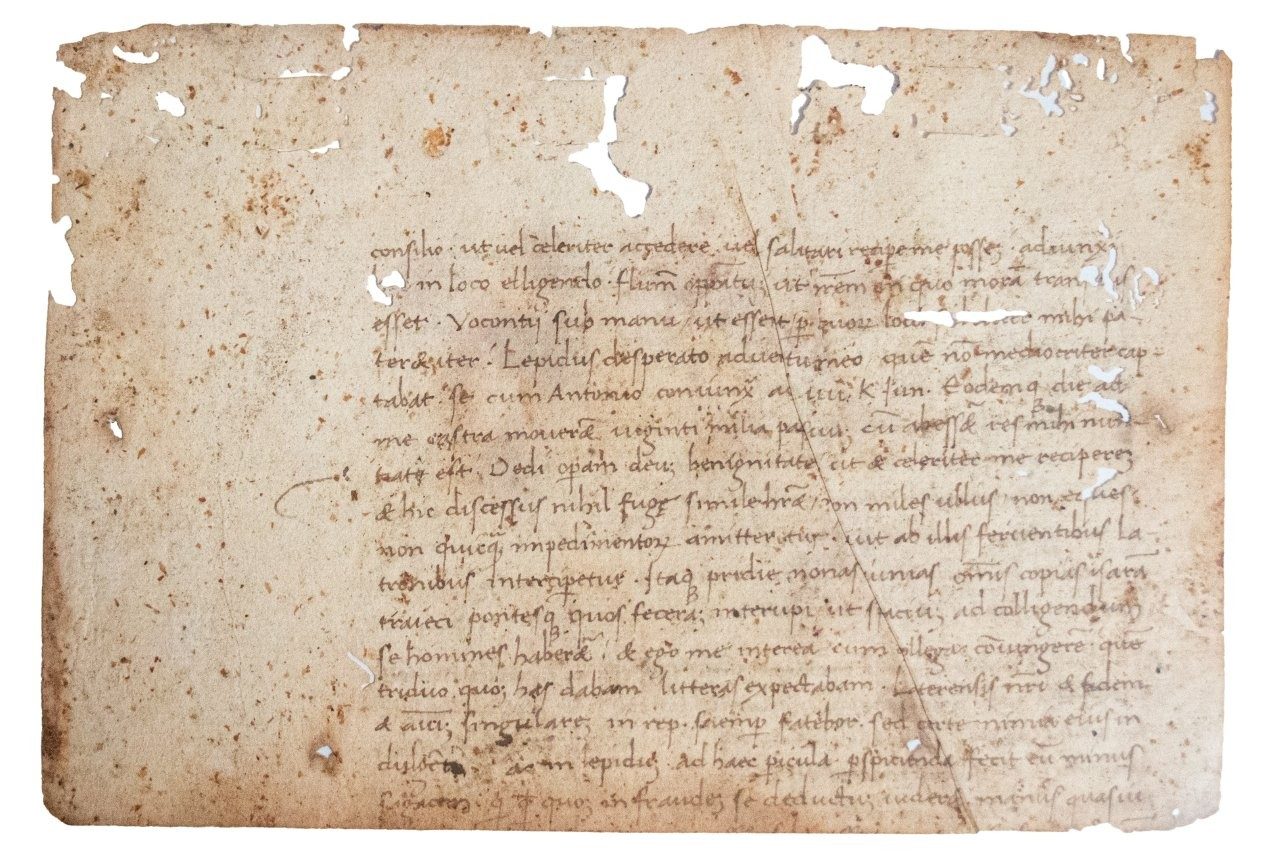

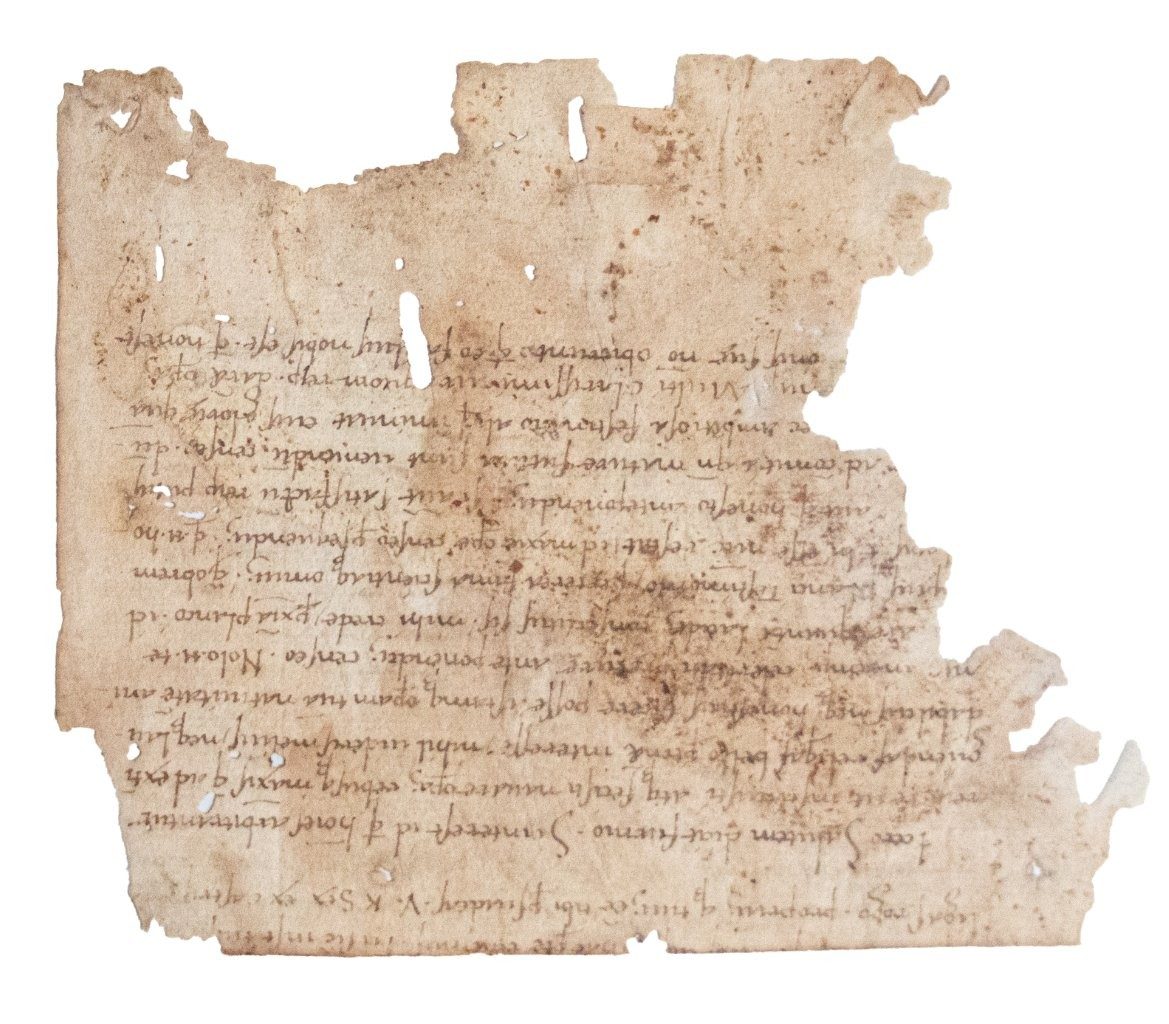

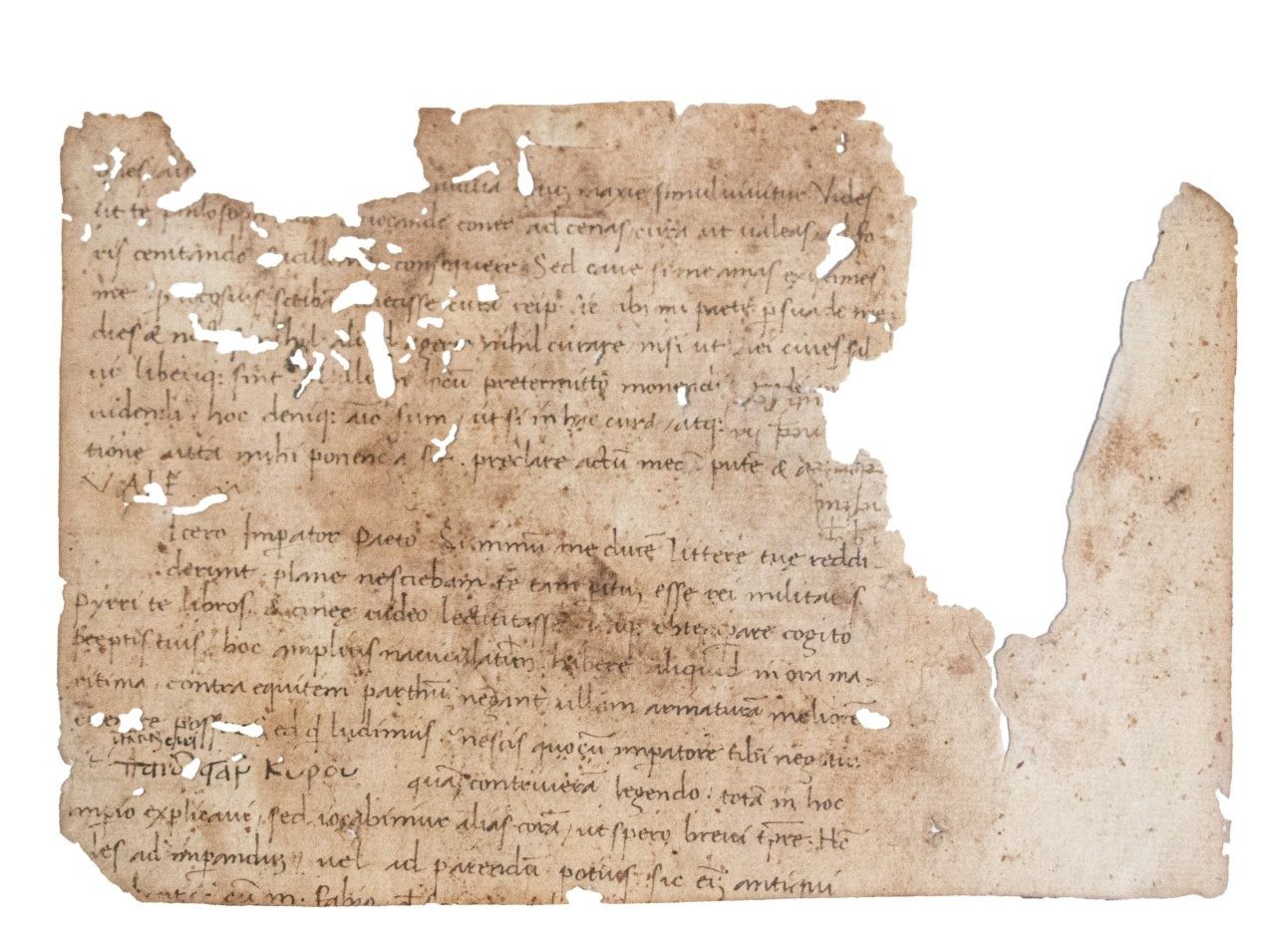

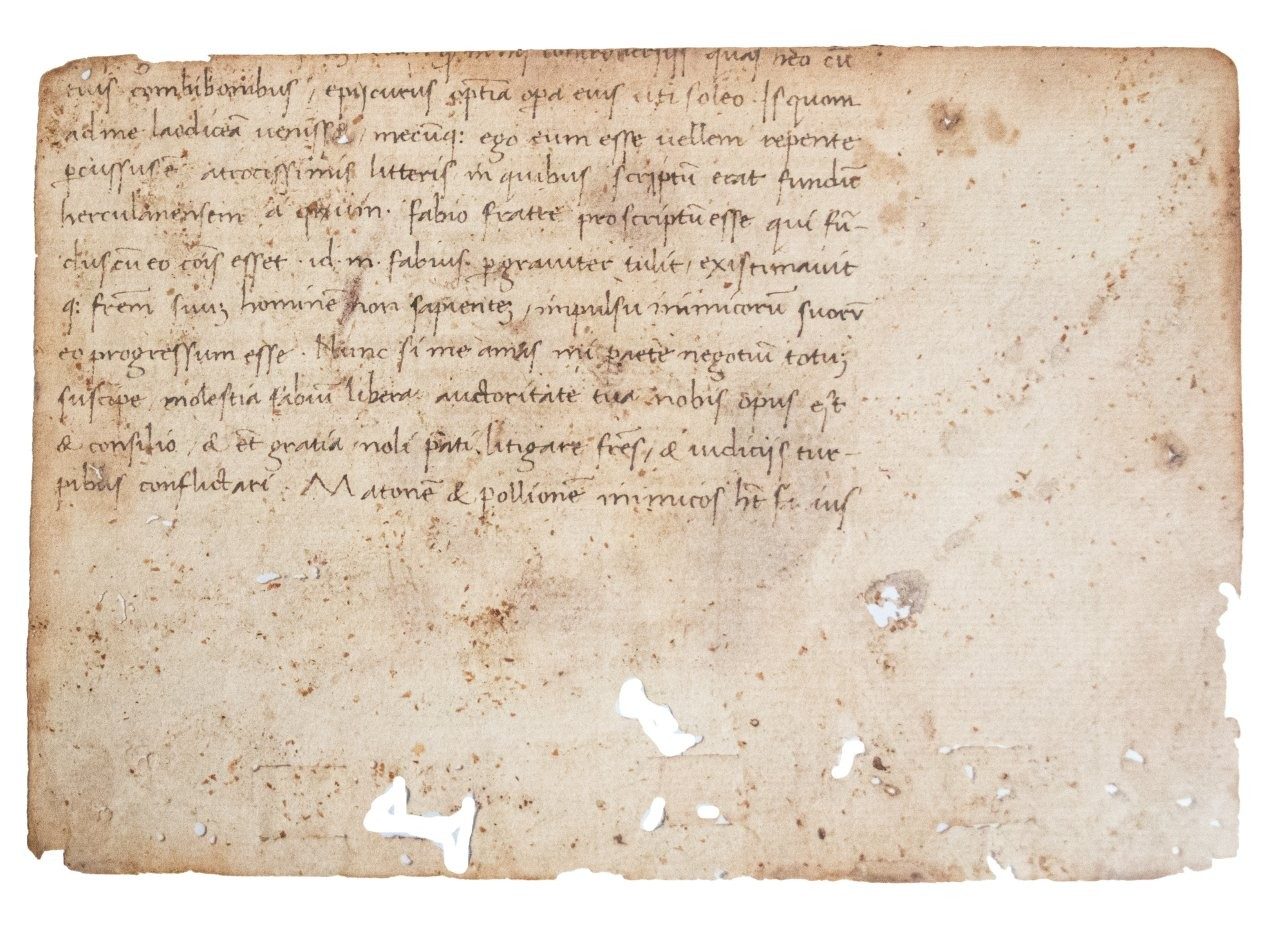

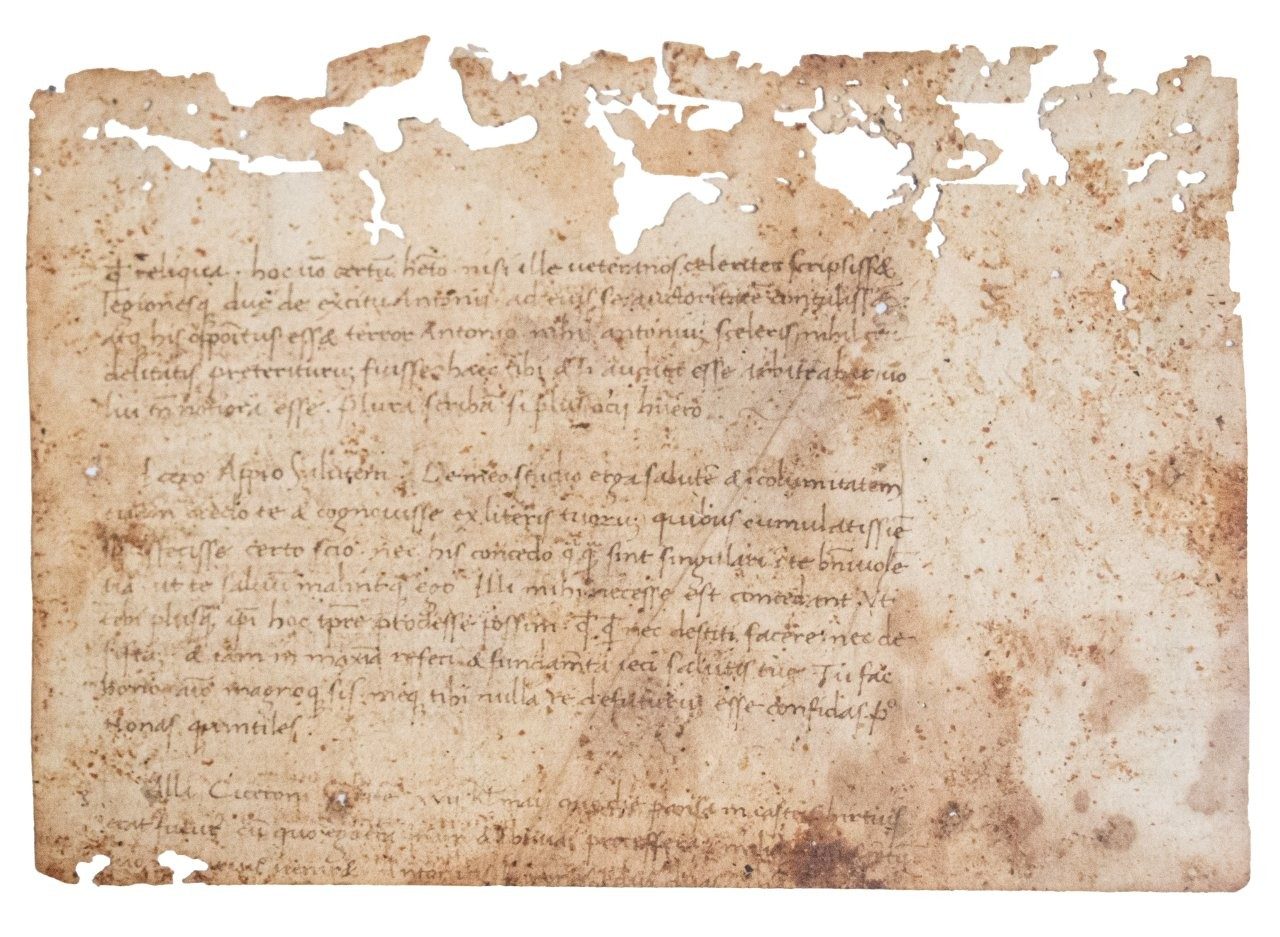

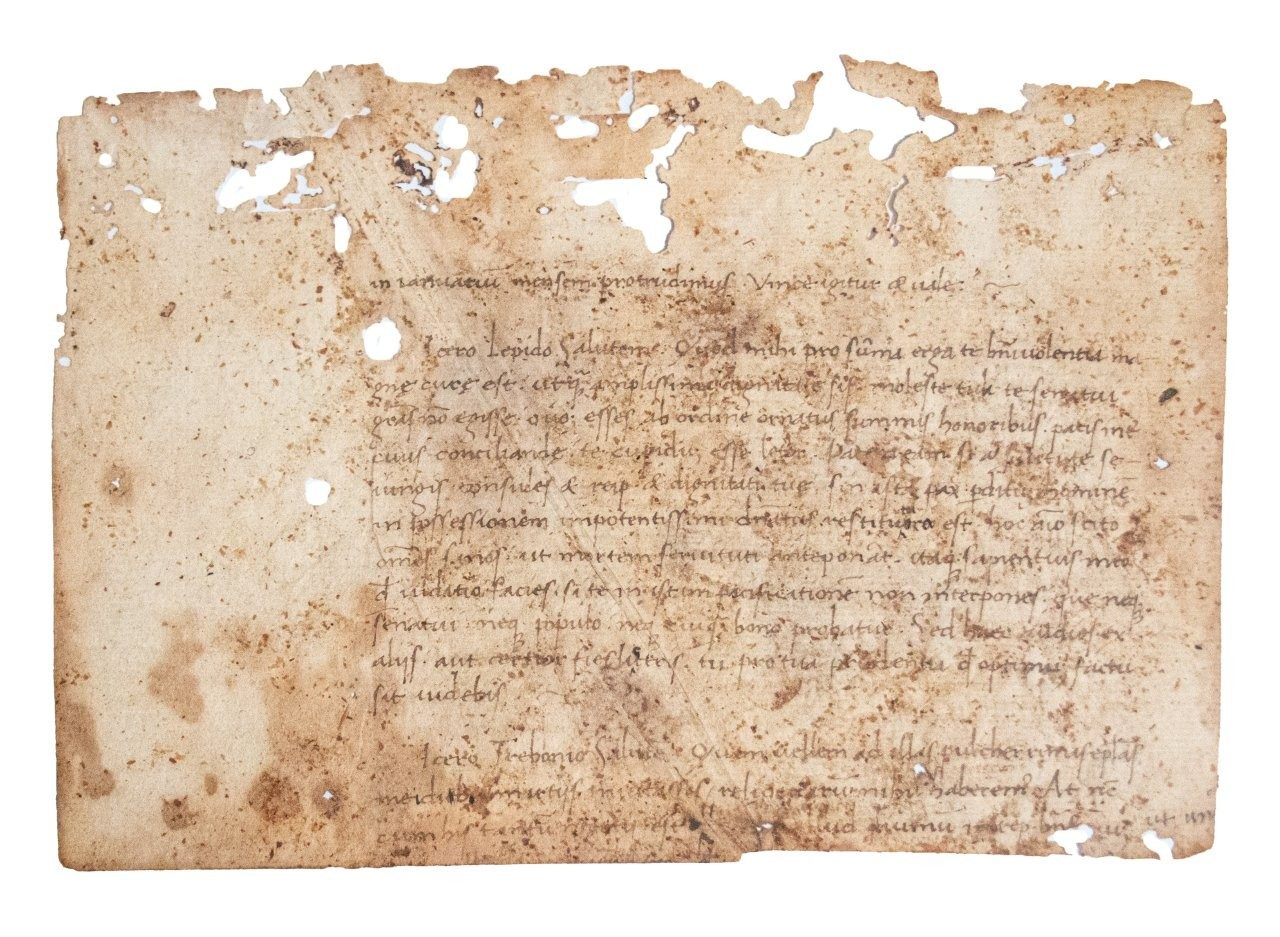

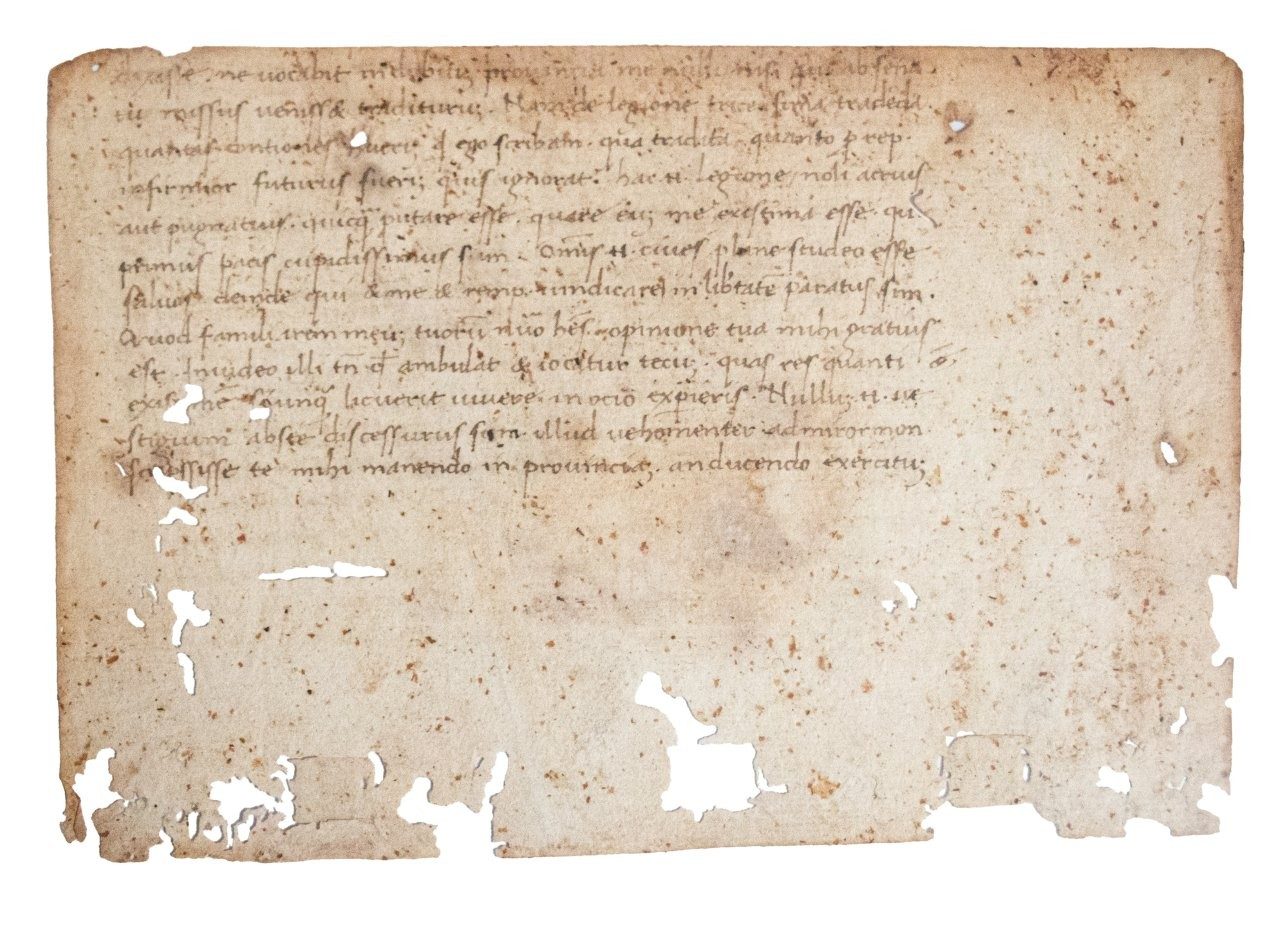

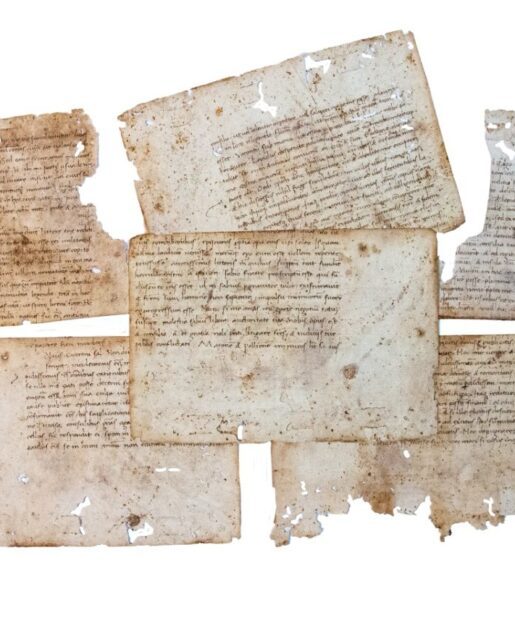

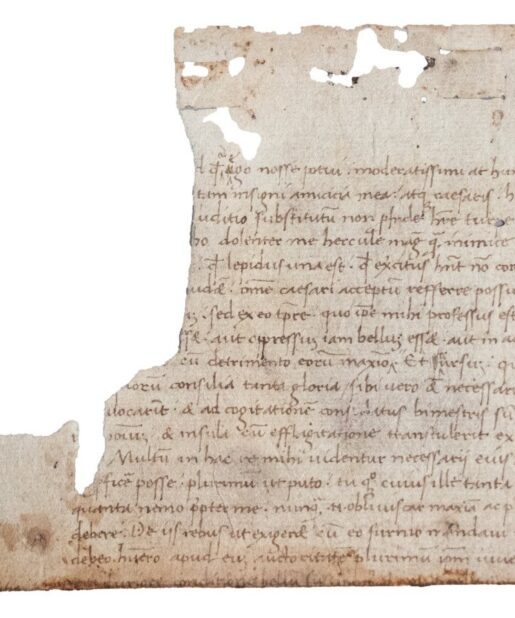

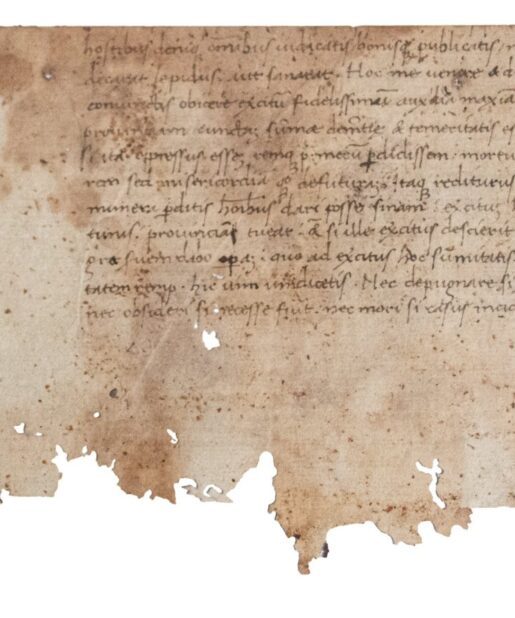

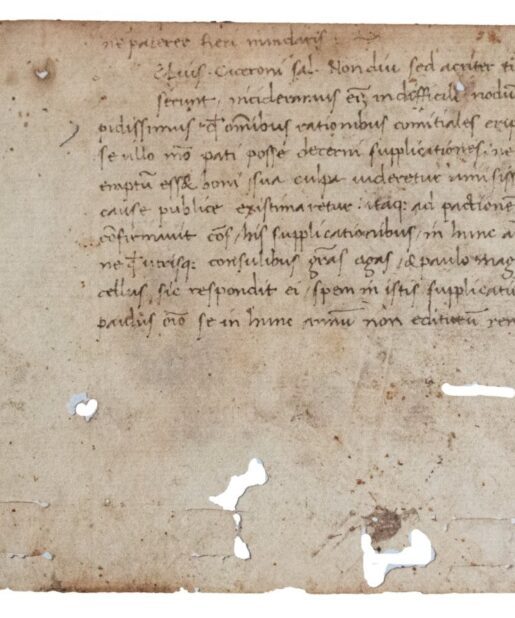

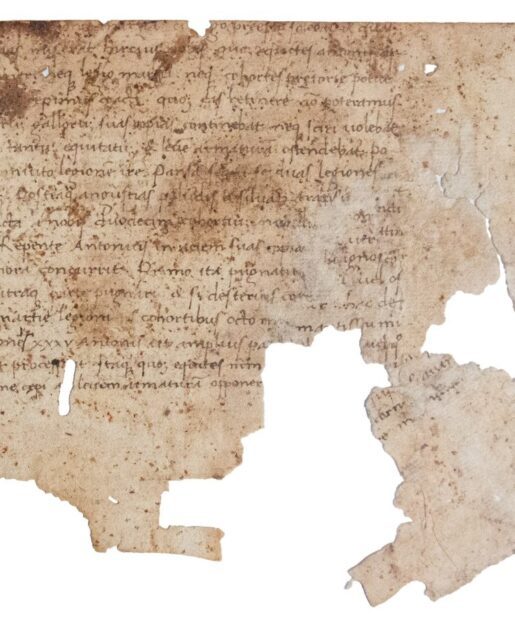

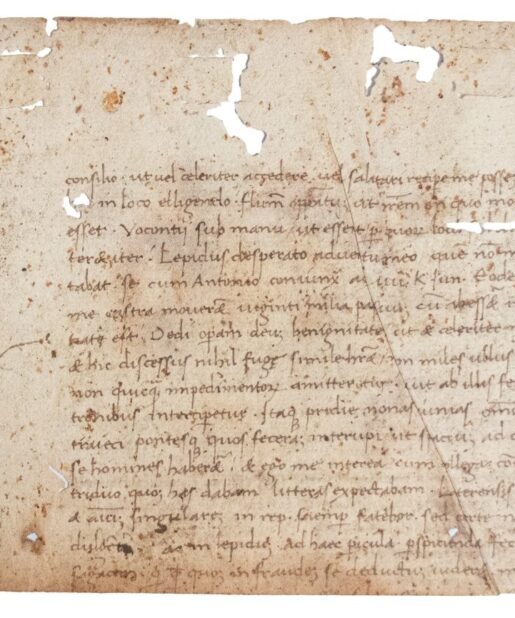

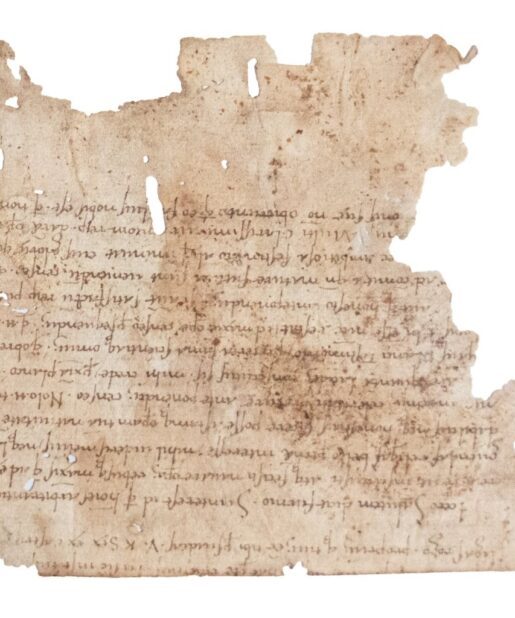

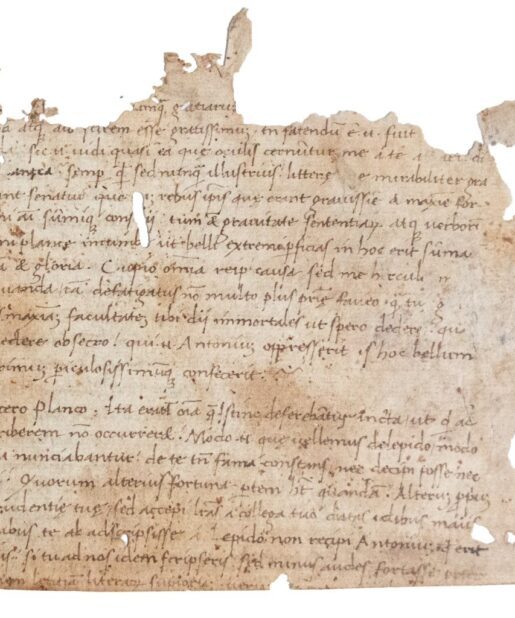

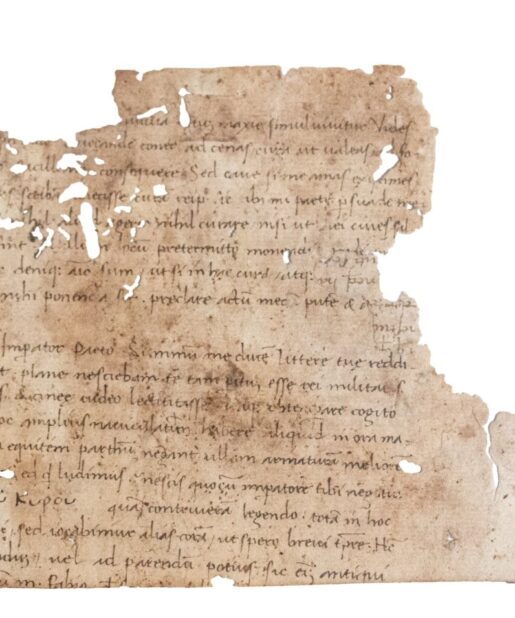

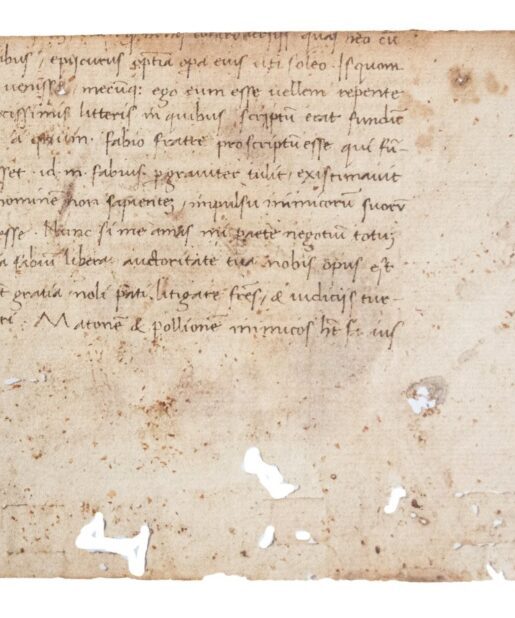

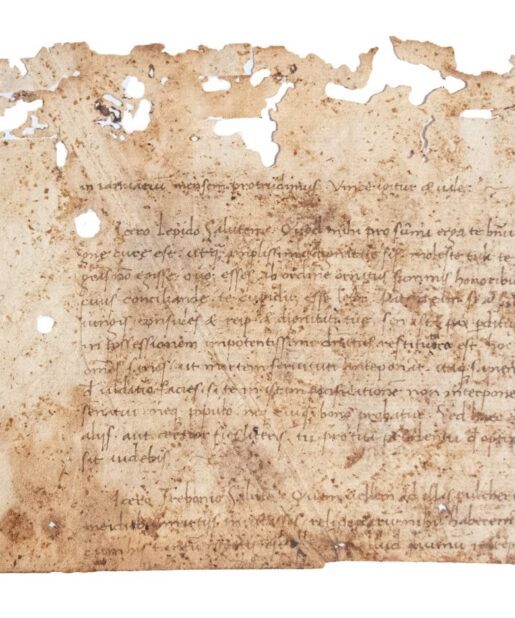

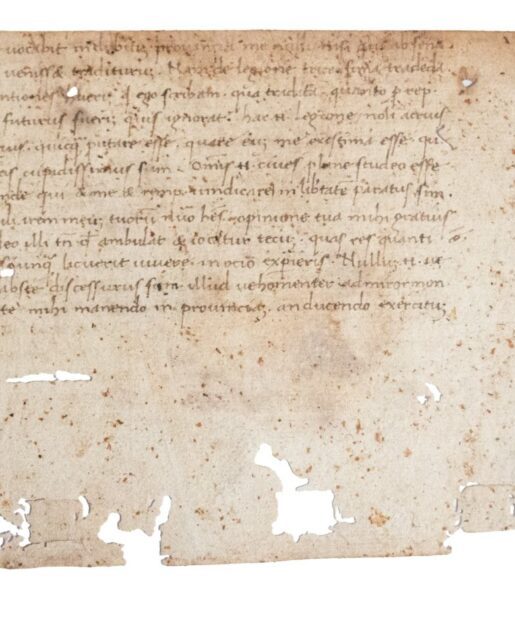

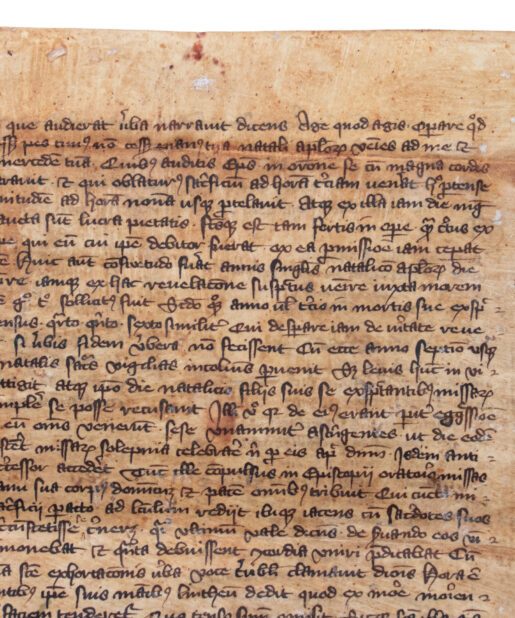

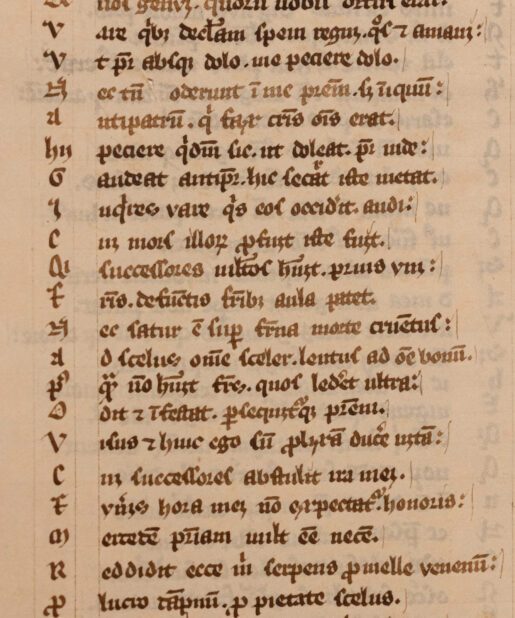

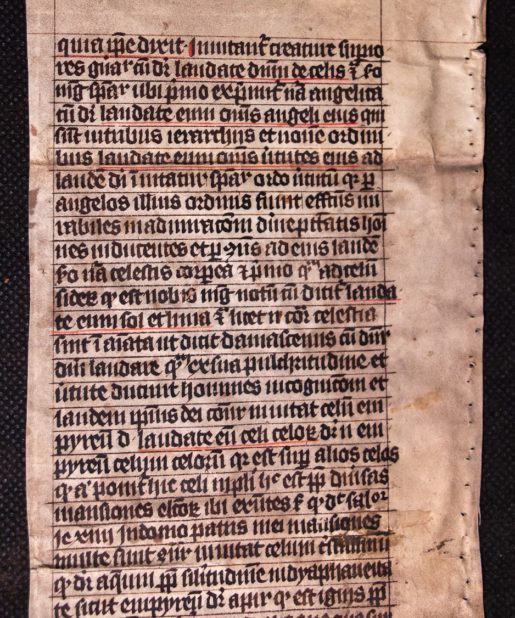

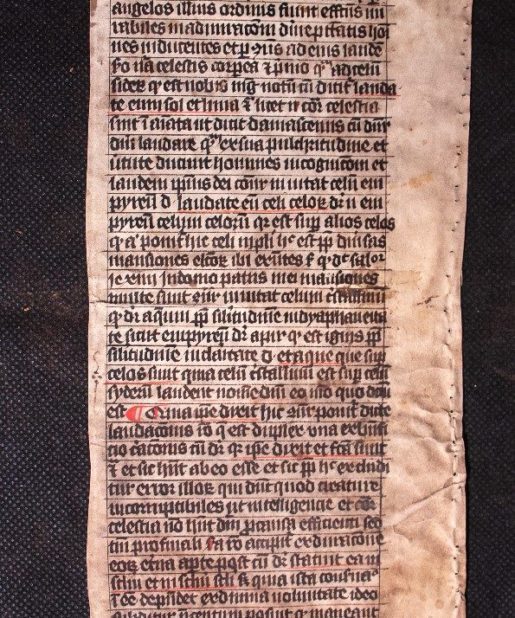

Cicero, Epistulae ad Familiares (letters to friends), 12 fragments of leaves from a manuscript on paper. Southern France or northern Italy, C15th

£2,500.00

Cicero, Epistulae ad Familiares (letters to friends), 12 fragments of leaves from a manuscript on paper. Southern France or northern Italy, mid-fifteenth century

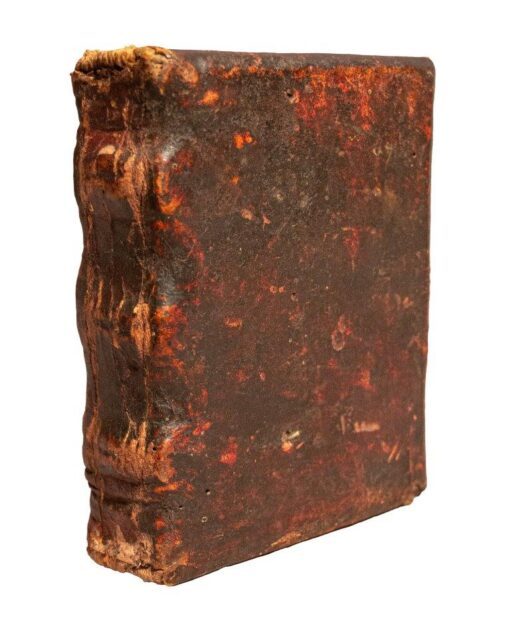

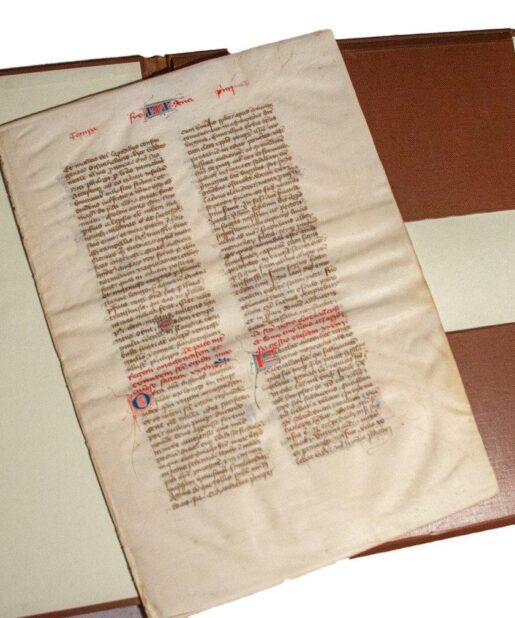

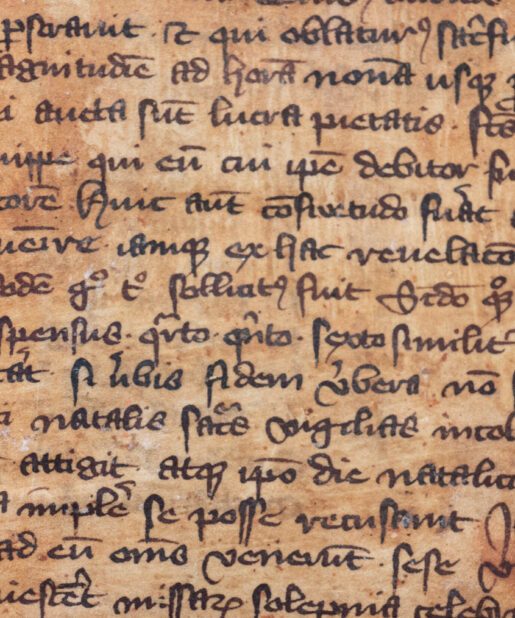

12 rectangular fragments, each approximately 185 by 120mm., from a single column copy of the text, with between 14 and 17 lines surviving of an accomplished humanistic hand, with a ‘g’ with an elongated and pronounced lower loop and a strong ‘ct’-ligature, most leaves preserving parts of upper or lower borders of parent manuscript, spaces left for initials, watermark of a bell-like flower with a stem with 2 leaves (split across gutter) close to Briquet 6641 (recorded in Sienna in 1434-35, Genoa in 1439, Le Puy in 1439-53 and Forez in 1439/69), all recovered from pasteboards in a later binding and with losses to edges, tears, small holes and with paper woolly in places, overall in fair condition.

Text

These letters, nearly 400 in total, sent by Cicero to friends and associates or received from them, are among the most important witnesses to the turbulent days of the failing Republic as well as to the inner psychology of Cicero as an individual. The collection includes formal letters to statesmen as well as political supporters and exiled friends and associates, ranging in subject from the mundanities of politics and securing political support to the murder of Caesar. However, many of these contain genuine feeling for the individual addressee, and the letter from Cicero’s friend Rufus, which attempts to raise Cicero from the depths of abject despair following the sudden death of his daughter Tullia, is still heart-rending some twenty centuries after it was written. Many were written out of the mood of the moment, with no thought for future publication, and offer an apparently open and unguarded insight into the mind of the writer.

They were collected together, organised and disseminated after Cicero’s death by his secretary Tiro (who was an author in his own right, and is credited with the invention of Tironian notation,

used throughout the Middle Ages). The text appears to have survived the collapse of the Roman world in only a handful of witnesses in northern Italian centres, and the earliest extant copy is a leaf from a fifth- or sixth-century uncial codex with an abridgement of the text (Turin, D.IV.22: Codices Latini Antiquiores IV: 443), which was at Bobbio in the seventh century, where its parchment was reused to produce a copy of the works of Augustine. In the ninth century there were evidently copies in various states of completeness in the library of the imperial abbey of Lorsch (see their library catalogue in Becker,

Catalogi bibliothecarum antiqui, 1885, p. 122, nos. 49-52), all most probably drawn from northern Italian codices. The complete collection descends from a single ninth-century manuscript at the head of the Lorsch list (now Florence, Laurenziana MS. 49.9), which by the early eleventh century had passed to Vercelli, where it was discovered by Pasquino de’ Capelli, chancellor of Milan, at the instigation of the grand Florentine humanist scholar and scribe, Coluccio Salutati (1331-1406: see A.C. De la Mare, The Handwriting of the Italian Humanists, 1973, pp. 30-43). In 1392, a copy was made for Salutati’s private library (that numbering some 800 volumes, and the largest in Florence at the time; his copy of the present text now Laurenziana MS. 49.7), and misorderings in the early binding of this manuscript – with disorder in the eighth and ninth books – allows the identification of that witness as the source of all Renaissance copies of the complete text, including the present manuscript. Here the scribe faced the challenges of his exemplar in an uncommon fashion, by omitting book 8 entirely while managing to restore book 9 without its heading.

Be the first to review “Cicero, Epistulae ad Familiares (letters to friends), 12 fragments of leaves from a manuscript on paper. Southern France or northern Italy, C15th” Cancel reply

Product Enquiry

Related products

C14th -C16th manuscripts

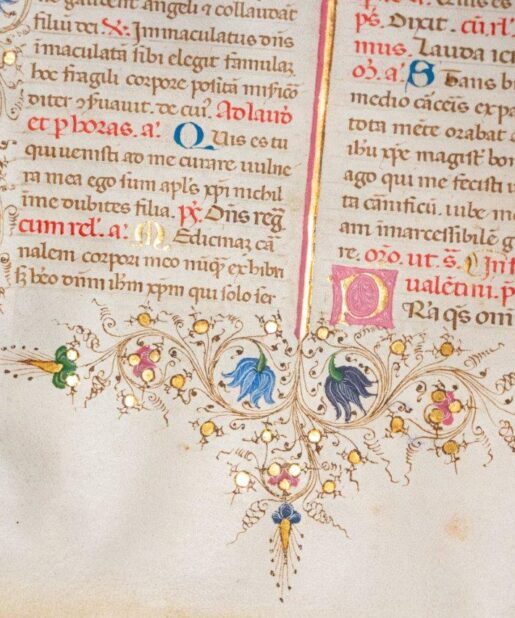

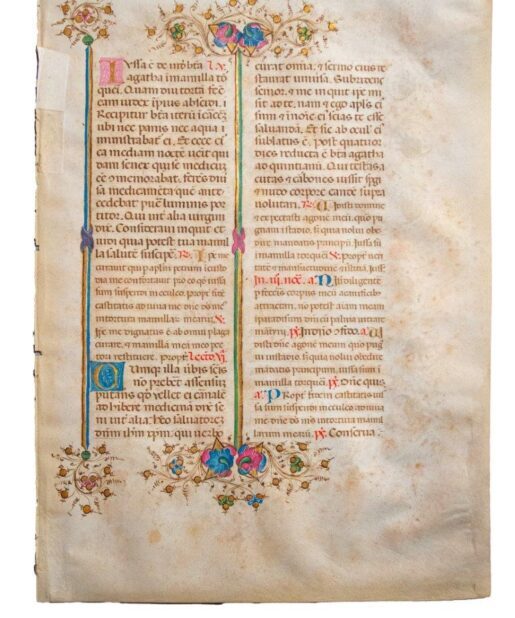

A fine leaf from the Llangattock Breviary, Italy c.1450 with delicate illumination on vellum

C14th -C16th manuscripts

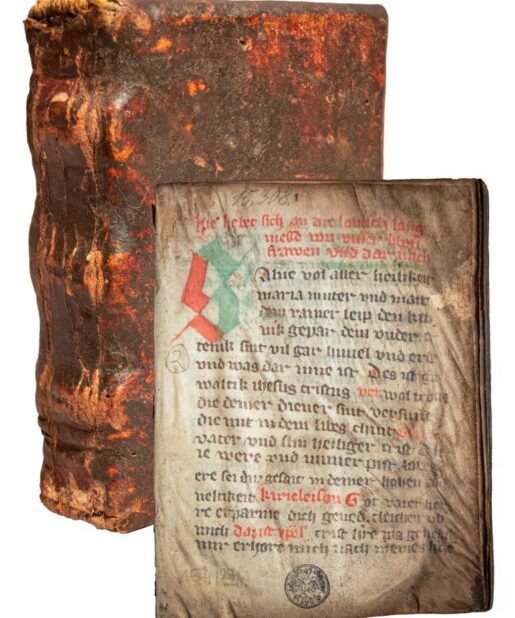

Unrecorded C14th German Book of Hours with C13th Ovid pastedowns

C14th -C16th manuscripts

C14th -C16th manuscripts

C14th -C16th manuscripts

C14th -C16th manuscripts

A C14th cutting from a Noted Breviary with music on a 4-line stave arranged around a red clef line

![Two fragments from Raymond of Penyafort (d. 1275), Summa de casibus penitentialis and Summa de matrimonio [Italy (or southern France?), 14th century] Two fragments from Raymond of Penyafort (d. 1275), Summa de casibus penitentialis and Summa de matrimonio [Italy (or southern France?), 14th century]](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/IMG_0096-515x618.jpg)

![Two fragments from Raymond of Penyafort (d. 1275), Summa de casibus penitentialis and Summa de matrimonio [Italy (or southern France?), 14th century] Two fragments from Raymond of Penyafort (d. 1275), Summa de casibus penitentialis and Summa de matrimonio [Italy (or southern France?), 14th century]](https://butlerrarebooks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/IMG_0095-492x618.jpg)

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.