Uncategorized

Carolingian Minuscule: The Key to Medieval Literacy

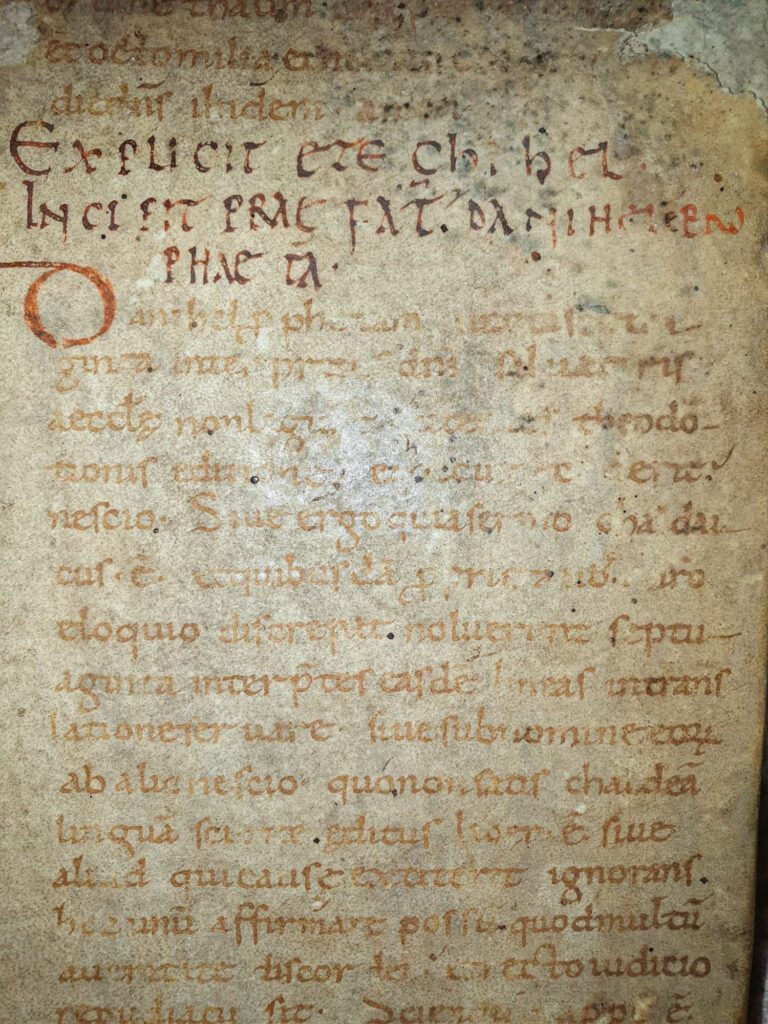

Carolingian minuscule, also known as Caroline minuscule, emerged in medieval Europe as a standardised script to ensure easy recognition of Latin texts, particularly Jerome’s Vulgate Bible, across different regions. Originating around 778 in the scriptorium of Benedictine monks at Corbie Abbey, and later refined by Alcuin of York during the Carolingian Renaissance, this script revolutionised communication and knowledge dissemination.

Derived from Roman half uncial and insular scripts used in Irish and English monasteries, Carolingian minuscule boasted legible, rounded glyphs with distinct letterforms. Emperor Charlemagne, recognizing the importance of literacy, supported its development, leading to features like word spacing, punctuation, and the introduction of lowercase letters.

Notable for its clarity and uniformity, Carolingian minuscule became the standard script for codices, religious texts, and educational materials across the Holy Roman Empire from 800 to 1200. Despite its eventual replacement by Gothic, it experienced a revival during the Italian Renaissance, influencing the development of humanist minuscule and serving as the ancestor of modern Latin letter scripts and typefaces.

Characterised by clear capital letters and word spacing, Carolingian minuscule aimed for cultural standardisation within the empire. Although it faced resistance in some regions, its influence spread widely, reaching as far as Slovenia and Switzerland, where local variations emerged.

The script played a vital role in preserving classical texts and facilitating the Carolingian Renaissance, with over 7,000 surviving manuscripts from the 8th and 9th centuries alone. Its enduring legacy can be seen in the humanist minuscule of the Renaissance and modern lowercase typefaces, embodying a bridge between ancient knowledge and contemporary typography.